by Elizabeth Goldsmith

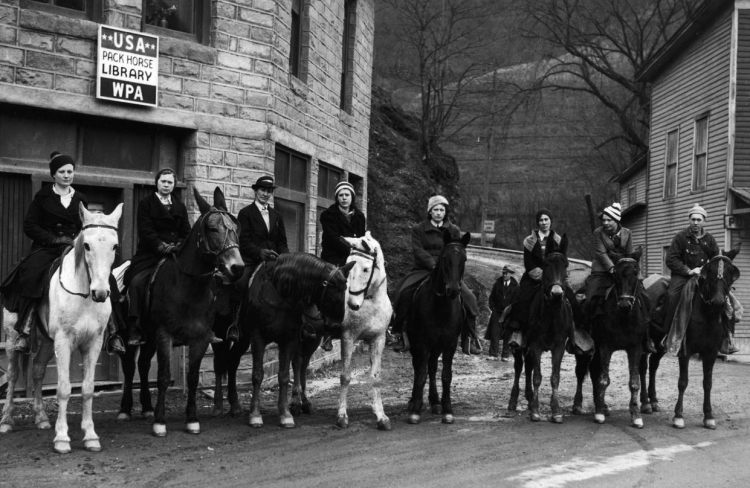

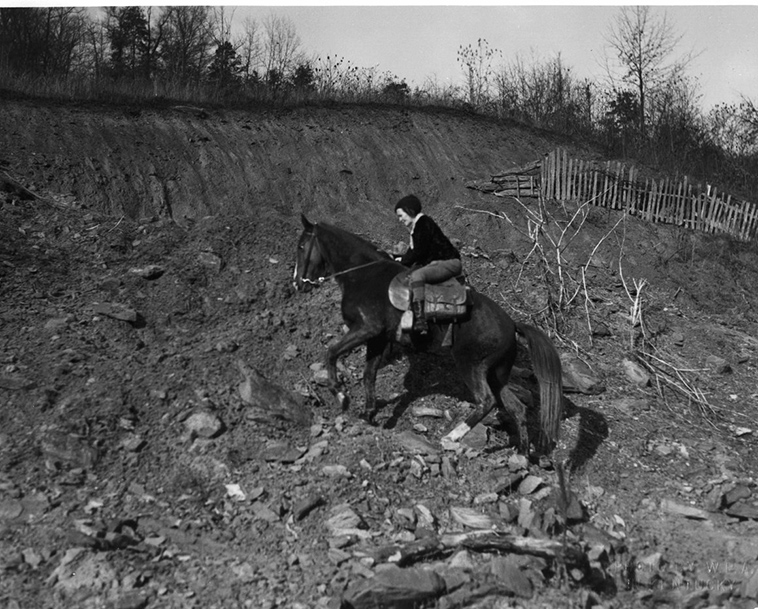

Wanted: Women willing to ride 100-120 miles per week through rural Kentucky, rain or shine, carrying library books to the state’s most isolated residents. Must provide own horse or mule and be prepared to walk if the terrain is too rough. Pay is $28 per month. Sound like something you’d like to do?

The Pack Horse Library initiative was part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), created to help lift America out of the Great Depression. Illiteracy was a real problem. In 1930 as many as 31% of eastern Kentuckians couldn’t read, although most wanted to learn. They saw literacy as their road out of impoverishment.

In 1936, packhorse librarians served 50,000 families, and, by 1937, 155 public schools. Children loved the program; many mountain schools didn’t have libraries, and since they were so far from public libraries, most students had never checked out a book. ”‘Bring me a book to read,’ is the cry of every child as he runs to meet the librarian with whom he has become acquainted,” wrote one Pack Horse Library supervisor. “Not a certain book, but any kind of book. The child has read none of them.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

Unusually, almost all the book carriers employed in the program were women — mostly local women as some of the mountain families distrusted outsiders and refused their materials. To gain their trust, librarians would read Bible passages aloud. For people who had only learned the stores of the Bible through an oral tradition, the idea that the Holy book was written down made their other materials more acceptable. More than just a delivery service, the Book Women were seen as educators who brought new ideas into rural areas and helped their patrons learn to read.

Popular books included books about travel, adventure, religion and romance magazine. Illustrated children’s books were also in demand because so many illiterate parents depended on their children to read to them. The biggest problem, other than accessibility, was quantity. A mere 800 books had to be shared among as many as 10,000 patrons. Because of the limited number of books, the communities created their own scrapbooks which included recipes and quilting patterns, along with cuttings from books and magazines. Eventually the collection included more than 200 of these self-made books.

The routes were tough going. Over the course of a month, women would ride and walk an average of 4,905 miles. It’s pretty amazing to think of these women out riding on their own, over terrain that was difficult and dangerous. Some of the Book Women were quite young and most were the family’s sole wage earner ($28 was the equivalent of $495 today).

“I got paid $28 a month and worked about three days a week. I had to hire my horse. I paid 50 cents a day for the horse, and fed it. It was just a big black horse. Bill, I think, was his name.” Grace Caudill Lucas doesn’t recall ever having any trouble with the horse, but she rode him around some cliffs so steep that, at some places, she got off and led him rather than risk a fall. And one of her patrons remembered her once riding the horse through water so deep that it reached the bottom of the saddlebags. Sometimes her feet froze to the stirrups. “I never did measure the territory, but it seemed like a whole lot of miles,” Lucas said. She was 22 years old when she became a book carrier.

In total, the program employed nearly 1,000 riding librarians. Funding ended in 1943, the same year the WPA was dissolved. The Book Women were sorely missed. Many of these communities were without library service until the 1950s when bookmobiles first came into use.

Read more about the Book Women and their fascinating role in history:

- The Women Who Rode Miles on Horseback to Deliver Library Books

- Horse-Riding Librarians were the Great Depression’s Bookmobiles

- Times Were Tough But the Book Woman was Tougher

Find more intestesting stories in our section on Recreation & Lifestyle.