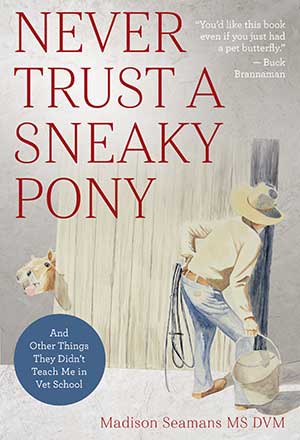

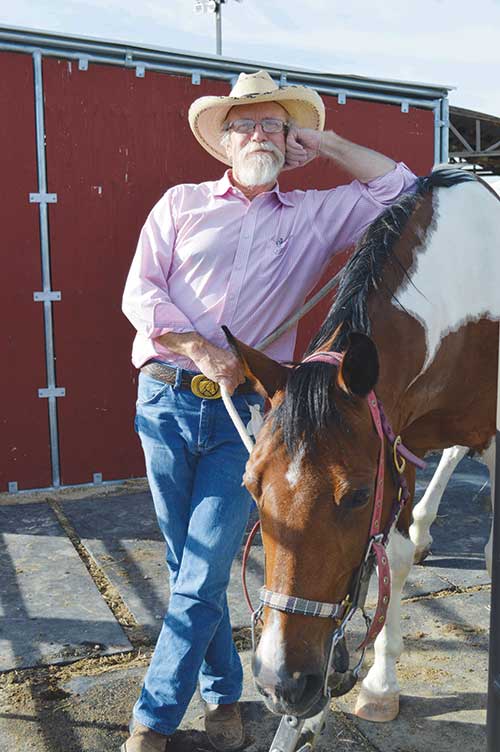

By Madison Seamans MS DVM

When I was a bright, young veterinarian just starting practice back in the eighties, I got a phone call from a man named Bob Gray who lived out of state. He asked me if I was available for a pre-purchase exam on a real good colt that he was thinking about buying. In those early days of my practice, this was like asking my cat if he was available for a can of tuna and a nap! I was so eager to practice medicine, I would have vaccinated his goldfish.

“When would you like me to look at this colt,” I asked while I thumbed through my nearly-empty appointment book. “I’ll try to work you into my schedule.” I took a deep breath and hoped that I had not violated some part of the veterinary oath.

“Any time would be okay with me,” he said. “I won’t be able to be there when you look at him, so just do it when it is convenient for you.” The voice came over the phone like a ray of hope, saving me from having to enroll in the Ace Truck Driving School to keep from starving. “The colt has some great bloodlines, and I am planning on using him as a foundation sire in my breeding program. If you find anything wrong with him, I need to know about it. This is a real expensive horse, and I don’t want any surprises. He’s just a yearling now, but I have a lot of hope for him.” Mr. Gray paused, then repeated: “He has great bloodlines.”

I had no idea that this last phrase would come to haunt me for years.

Bob gave me the name and phone number of the lady who owned the colt in question. I called Carla, and we made an appointment for later in the week. She was friendly enough but let me know clearly that there was nothing wrong with the colt. If Mr. Gray considered a prepurchase exam necessary, that was “all right with her.”

I have never considered myself a distrusting fellow, but I have been involved in enough horse trades over the years to realize their potential to bring out the scariest parts of human nature. In addition, I have purchased enough lame, crazy, crippled and just overall bad horses to become, well, “cautious” when dealing with the buying and selling of horses.

For example, when I was still a student, way back in the early seventies, one of the ways that I supported my college habit was by riding colts for people and trading a few horses myself. One time I bought a big, stout, red, four-year-old gelding that I called Red Man. I rode him for quite a while as he had about every bad habit a horse could have. When I finally sold him, he was about fifteen years old. I didn’t ride him that long, he just wasn’t that young! I took quite a beating physically and economically, as this old snide had crippled a couple of local cowboys before I got him, and he hadn’t seen his fourth birthday since LBJ was president.

Some of life’s best lessons are also its toughest, and I was lucky to have survived that one. It did motivate me to learn how to tell the age of a horse by looking at his teeth, and I got pretty good at it out of economic necessity.

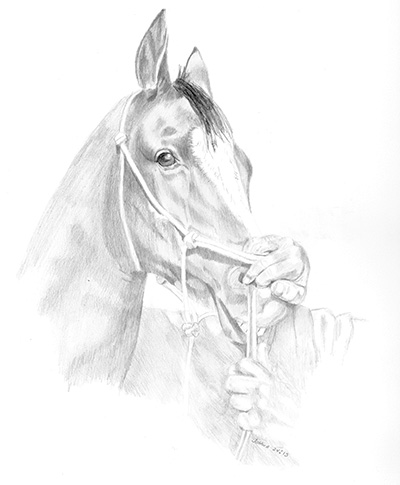

A horse has three pairs of incisor teeth that are easily seen in the front of his mouth. These are named from the center of his mouth outward. The central pair are, of course, in the middle, the intermediate pair are next, to the left and right of the centrals, and the corners are on the extreme outside. They are the same for both upper and lower jaws. A foal is born before any incisor teeth are erupted, but they appear fairly predictably, though variations occur. Any broodmare will tell you that the central pair of incisors will erupt in a foal about the seventh day of life. (Readers that have nursed a child know the sensation!) Most lactating mares agree that this is way too soon for their own comfort, but it is part of the foal’s natural growth process, and the mares seem to survive in spite of it. The intermediate pairs erupt at about seven weeks, and the corners at about seven months. These are all “deciduous,” or “baby,” teeth. Adult teeth replace their deciduous predecessors in an equally predictable fashion at two and a half, three and a half, and four and a half years in the same order, from central to intermediate to corner pairs, respectively.

Baby teeth are smaller, whiter and more “pinched” at the gum line than adult teeth. So with practice, it’s not difficult to learn how to age a horse with a fair degree of accuracy. After a horse has reached the age of ten, there is more guess work involved, but, up to that time, it would be unusual for an experienced hand to be more than a year off in estimating the age of a horse by his teeth.

I arrived at Carla’s ranch at the appointed time to examine a big, stout, clean-legged colt. It was easy to see why Mr. Gray was interested in this colt as a stallion prospect because he sure was nice. He moved around the lot like his feet just barely touched the ground, and his long, flowing mane and tail gave me the impression that he was on the verge of flying. He was a little snorty, and I had to rope him in a small pipe corral to catch him. Carla said that they had weaned him late, and they hadn’t taken the time to handle him much. Not only was he hard to catch, he was pretty narrow-minded about any kind of veterinary examination. He would not let me pick up his feet, or listen to his heart and lungs, or even look in his mouth.

“Maybe we could watch him move around in the round ring,” I suggested, “and let him blow off a little steam so we can examine him.”

I watched the colt run around and over the ranch hand on the way to the round pen, and I admired the athletic ability of both of them. After about forty-five minutes of watching this colt circle the man at nothing less than a dead run, he slowed down a little, and I thought that maybe I could complete some kind of exam on him. We steered him back into that little bitty pipe pen, with the hired hand leading and me driving him from behind by waving my hat and clucking at him when he balked. It looked to me like this was the colt’s first lesson in leading, and it wasn’t much easier to approach this time than it had been earlier.

I had handled a few salty colts, so I was used to the certain lack of enthusiasm that some horses have for human contact. I was beginning to wonder just how old this colt was, because he sure seemed big for a yearling, and he had that beautiful long, flowing mane and tail. Anyone that has ever had a tail chewed off a show mare by a colt or a bored stablemate can tell you that it takes a long time to grow much tail. (That is the reason that so many show horses go around with their tails braided and in protective wraps or bags.) Anyway, this colt was not about to tell me how old he was, and he was in no mood for a dental exam.

With the help of the hired hand, I got a “twitch” on the upper lip of this good-but-reluctant colt. A twitch is a rather barbaric-looking, clamping or twisting apparatus that is sometimes placed on the upper lip of an uncooperative horse. I almost never use these things because I believe that patience and finesse are superior to brute force, but I was running out of both of those virtues, and I couldn’t think of another way to look in this colt’s mouth. The twitch calmed him down considerably. He bit at me a few times, but I did get a good look just before he struck at me with both front feet.

Just as I had suspected, he had adult central incisors and was in the process of shedding his intermediates. With all the diplomacy I could muster, I suggested to Carla that there must be some mistake because the horse Mr. Gray was interested in was a yearling, and this colt was about to turn four years old.

“No he’s not,” she said coolly. “He’s a yearling. He has excellent bloodlines, and I have the papers to prove it.” And she did, too—she showed them to me like she fully expected that it would change my mind. Butter wouldn’t have melted in her mouth for a couple of days. This lady was unflappable.

“I can’t argue that you have the papers for some yearling colt, but this ain’t him!” I exclaimed, with some of my diplomacy waning. This lady’s attitude was making me more suspicious by the minute. She was just too complacent about the whole thing. If somebody had pointed out such a discrepancy about one of my horses, I would have become a little agitated, at least.

But she just looked at me.

All the way back home, I wondered about what had just happened. I could be six months or a year off in my estimation of the colt’s age, but not two and a half years!

I called Bob Gray later that evening.

“Well, what did you think about the colt?” he asked.

“He’s not a bad horse,” I said. “In fact, I was rather impressed by the colt I looked at, but he may not be what you think he is. Have you ever seen him?” I asked.

“Well, no, not in person,” he said. “I’ve seen pictures of him, and he has outstanding bloodlines,” he added that line again. Then, “What do you mean, ‘He’s not what I think he is’?” he asked after a long pause.

“The horse Carla showed me today is coming four this spring. He’s not a yearling.”

“That can’t be!” He was shocked. “He has such good bloodlines. There must be some mistake.”

By now, the genetics of the situation was becoming rather amusing. I was beginning to wonder what happened to the horse that matched the papers they were trying to pass off with this colt. After all, an unregistered four-year-old is worth a lot less than a yearling “with such good bloodlines” and all the papers to prove it.

“Well,” he said, “thanks for all your help, Doc. Go ahead and write up the health papers for him, please. I’d like to ship him out here right away.”

I did and he did. I don’t know how this horse did at stud, but I wonder if his papers really improved his popularity.

This excerpt from Never Trust a Sneaky Pony by Dr. Madison Seamans is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (HorseandRiderBooks.com).

There are so many great reads in our section on Books.