by Gene Fowler

Standing in front of Frederic Remington’s 1889 oil painting, A Dash for the Timber, at Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art, I am reminded of the words of a California friend. “You’ve got to see these things in person.” I’d written him about a new book about a West Coast artist we like. The book is nice, he allowed, but you’ve got see these things in person.

Boy howdy. Riding hell-for-leather and pursued by a Native American war party in Remington’s seven-foot-wide piece, the eight desperate horsemen of A Dash for the Timber seem a split-second away from stampeding off the canvas and right over the viewer. Seeing the painting is visceral. Even New Yorkers were spellbound when the work debuted in 1889.

My friend’s gentle dictum resonated again as I beheld The Medicine Man, Buffalo Bill’s Duel with Yellowhand, In the Wake of the Buffalo Runners, and other paintings by Charles M. Russell at the Amon Carter and the Sid Richardson Museum, the latter located on Sundance Square in Fort Worth, aka Cowtown. The richly-shaded, long-range landscapes and vast, big country skies of Russell’s original canvases draw one in as no mere reproduction may.

The august Texas folklorist, J. Frank Dobie dubbed Remington (1861-1909) and Russell (1864-1926) the “Titans of Western Art” in 1964. Former Amon Carter curator Peter Hassrick, who jokes that he got out of Texas as soon as possible so that his kids would not “tahk lak Tayxuns,” says that late 19th and early 20th century aficionados of frontier art were often either “Remington people or Russell people.” I would liken the double-barrel matter of individual taste to the popularity contest among singing cowboys a half-century later, when silver screen and T.V. shoot-em-up devotees would often swoon and root for either Gene Autry or Roy Rogers.

Both artists grew up in affluent settings, Russell in St. Louis and Remington in New York State. Both shared and acted upon what one historian termed “the dream of every adolescent male in the whole 19th century,” the restless desire to head out West and be a cowboy. Remington left Yale after a year and a half and trekked to Montana; later, he briefly owned a Kansas sheep ranch and then a Kansas City saloon, making sketching trips into “Indian Territory” (now Oklahoma), before retreating back East.

A teenaged Russell headed for Montana in 1880, spending more than a decade as a night wrangler in the Judith Basin and learning the cowboys-and-Indians life as only an extended boots-on-the-ground investment would allow. Known as “the Cowboy Artist” from the early days of his career, some of the young painter’s first studios and galleries were in saloons. After marrying 17 year-old Nancy Cooper, who soon became the artist’s naturally gifted manager, Russell spent the rest of his life headquartered in Great Falls, Montana, where he painted and sculpted in a log cabin studio. The Russells often spent summers in another cabin, Bull Head Lodge, in Montana country that eventually became Glacier National Park. In his last years, they built a home in Los Angeles called Trail’s End, but the artist died before he could live in it.

Working as an illustrator for Collier’s, Leslie’s, Harper’s Weekly and other leading periodicals of the day, Remington, though based in Brooklyn and then New Rochelle, New York, made frequent trips to the West, the Southwest and Mexico on magazine assignments. He was embedded, for instance, with the Ninth Cavalry during the Apache Wars of the mid-1880s. In his 1994 book on the Sid Richardson Collection, Remington & Russell, Western art scholar Brian Dippie observed that Remington’s “influence in shaping the West of the popular imagination cannot be overstated.”

However, Dippie added, “Remington’s was a West without much softness or subtlety. It was, instead, a grand theater for the testing of manhood…a throwback to pioneer days, the molding of the national character and the setting for a great drama. The winning of the West was his theme, and he never outgrew it.”

As biographer John Taliaferro summed it up in his 1996 book, Charles M. Russell – The Life and Legend of America’s Cowboy Artist, “Remington had better command of color and was a superior draftsman,” but “in his Western work at least he strove to communicate only militancy, danger and dread. Charlie’s untrained hand was forever guided by sympathy.” Taliaferro also credits Remington with creating a market for Western art and with being a major influence on Russell. And the biographer notes that the New Yorker established authenticity as the genre’s hallmark, a characteristic that was Russell’s strong suit, but which Remington’s own creations sometimes lacked.

However their artistic legacies shake out, I sure am glad that Amon Carter, who started out in newspaper publishing and then made a pile of dinero in oil, and wildcatter Sid Richardson established museums in my general neck of the cactus patch that provide the opportunity to experience so many original works by the Titans of Western Art. We can thank Charlie Russell’s friend, Will Rogers, for inspiring Amon to begin collecting. As biographer Jerry Flemmons reports in AMON – The Texan Who Played Cowboy for America, Carter bought his first Russell works in 1928, just two years after the Cowboy Artist’s death. In 1952, Amon bought out the entire artwork inventory of the historic Mint Saloon in Great Falls, Montana.

Eventually Carter acquired some 400 works by Remington and Russell, described as the cornerstone of the museum’s collections today. Some 21 oil paintings and several dozen bronzes are currently on permanent exhibition at his namesake museum. In addition to Remington’s A Dash for the Timber, I was especially drawn to his circa 1905-1906 oil, Ridden Down. Standing on a bluff above a desert floor of pulsating, yet muted wavy yellow haze, an exhausted warrior stands beside his lathered horse. Covered with green and yellow medicine paint and awaiting his fate at the hands of the war party raising dust below, he gazes toward the heavens as though entreating the spirit world to prepare to accept him into its domain.

Peter Hassrick notes that in his final years Remington’s perspective on the Native Americans changed. While he once viewed them as antagonists in the path of America’s Manifest Destiny, he eventually viewed and painted them more as Russell did, as a proud people with dignity. And Ridden Down evidences that shift.

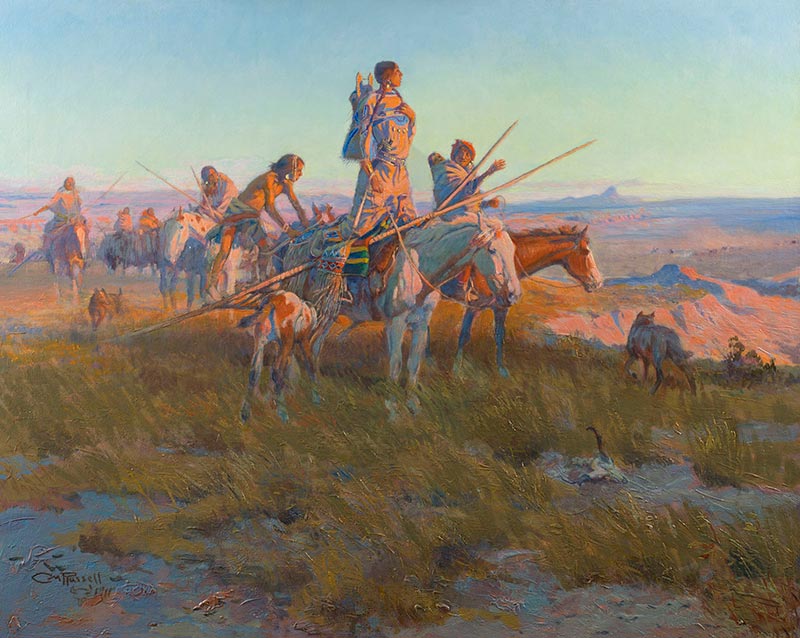

Russell’s 1908 painting, The Medicine Man had me at “medicine man.” It depicts a band of Blackfeet, a tribe the Cowboy Artist had closely observed in Montana’s Judith Basin. Haystack and Steamboat Buttes are visible in the background and the medicine man’s details include his ceremonial crooked lance, a pronghorn medicine pendant around his neck and white ermine skins with a prairie chicken feather medallion on the side of his head. The designs on his face and body are painted with vermilion and he carries a decorated buffalo robe on his saddle. A warrior behind him wears a coat made from a Hudson’s Bay blanket.

Russell himself considered The Medicine Man one of his best works. “The medicine man of the plains Indians,” he wrote, “often had more to do with the movements of his people than the Chief and is supposed to have the power to speak with spirits and animals….”

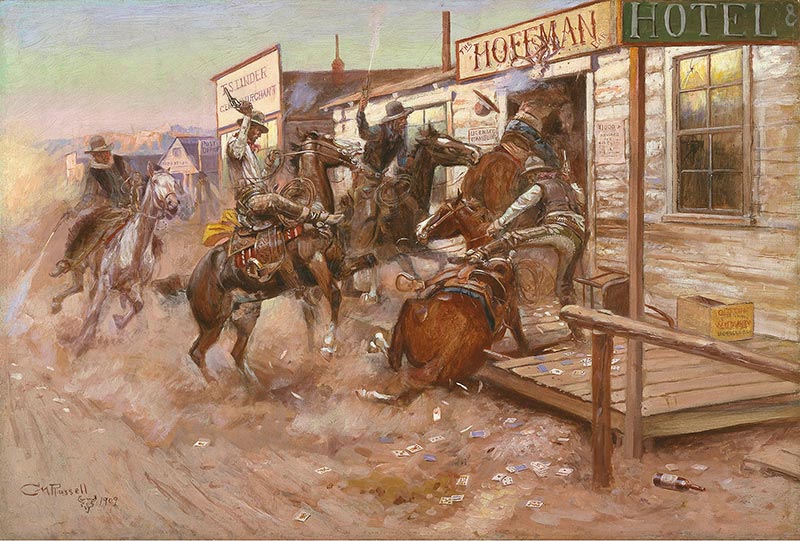

Such painstaking detail is also evident in Russell’s 1909 work, In Without Knocking. Based on a real saloon entry perpetrated by Russell and his fellow Judith Basin round-up riders in Stanford, Montana, the ride-your-horse-into-an-establishment practice was a fairly widespread pastime throughout the West. This particular scene was reenacted in a Tom Mix movie, complete with one horse busting its hoof through the wooden sidewalk. The second cowboy from the left wears a Montana short-brim peak hat, and his folded-up pant leg recalls “one-size-fits-all” britches marketing. The cantle of his saddle has a rattlesnake skin cover, a folk medicine practice originating in Texas and Mexico that was believed to prevent saddle sores. Playing cards and poker chips litter the ground.

Pull-out drawers in the Amon Carter gallery display several examples of Russell’s famous “illustrated letters.” An inveterate sketcher who drew on whatever was available, the Cowboy Artist’s correspondence was published posthumously as a book entitled Good Medicine. Shown here is a letter to his friend Guy Weadick, a former trick roper with the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch Wild West Show and founder of the famed Calgary Stampede.

Sid Richardson, active in both oil and cattle, wildcatted the art world for his Western collection from 1942 until his death in 1959. “His affinity for their work is easily explained,” wrote Brian Dippie in Remington & Russell. “Richardson had trailed cattle in his youth, camping out under the stars with his saddle for a pillow.”

“I get a kick out of seein’ ‘em around me,” Richardson testified. He hung Russell’s Man’s Weapons Are Useless When Nature Goes Armed, which depicts skunks destroying a campsite in search of food, in the dining room of his island home on the Texas coast to “bug” his older sister. But he especially appreciated a good rendering of a horse in action. “Anybody can paint a horse on four legs,” he once said, “but it takes a real eye to paint them in violent motion….and Remington and Russell are the fellows who can do it.”

The three dozen paintings and sculpture by the “Titans” currently on view at the Sid Richardson Museum represent about a third of his collection. The show will be up until September, when another third will rotate into the galleries. Docent Beth Haynes pointed out a row of Remington nocturnes, painted in the last years of his life. Though he had been a successful artist for some time, Haynes explained, critics had complained about the way he mixed his paints. But when they saw A Taint of the Wind (1906) and other Impressionist, impasto-deepened night scenes, the docent continued, any previously unconvinced critics at last acclaimed him a great American artist. “You look at the scene, with the horses all startled by something off to the left, and the stagecoach riders hidden in the darkness, and your eye wanders off the frame,” Haynes marveled. “You create a story in your imagination about what happened.”

A friend of Remington’s wrote that his nocturnes “were keyed to the mute though not inglorious poet in him.” The seven chanting, singing men, gathered round a campfire, beseeching the spirits for bountiful crops in Apache Medicine Song (1908), indicate a more ethnographic interest than his earlier work. Late in his short life, he seemed more appreciative of the mysteries of these cultures so alien to his own.

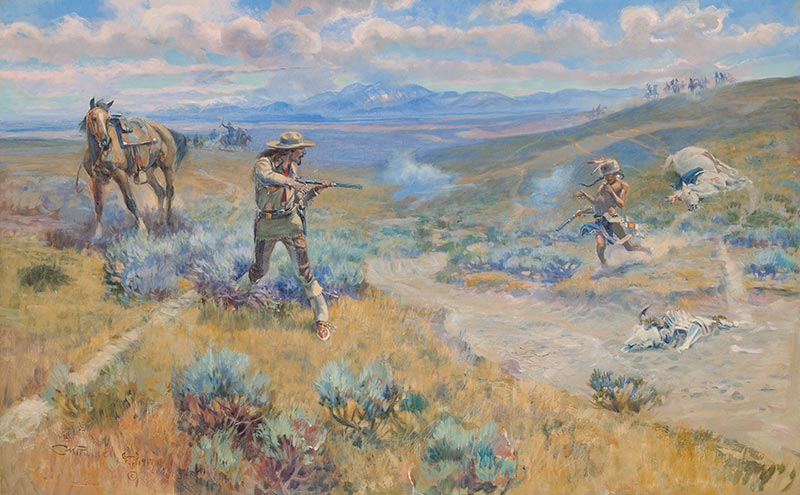

Russell’s first commissioned work is included in the current Richardson exhibition. Painted with house paint on pine board, Western Scene (1885) is a triptych depicting Native Americans firing on a circled-up wagon train and wildlife scenes of elk and pronghorn antelope. A 1917 oil, Buffalo Bill’s Duel with Yellowhand, was painted the same year the old scout turned showman died. In a haze of soft blue and gold tones, with smoke drifting off from discharged firearms, the painting re-created an 1876 encounter between Buffalo Bill and a man originally identified as Yellow Hair, which had been redecorated and revised with innumerable retellings over the intervening 41 years.

Brian Dippie describes In the Wake of the Buffalo Runners (1911) as “one of Russell’s greatest paintings,” and I have to agree. I love the way that the fading, yet still rich and golden light falls across the men and the landscape and bathes with amber beauty the horses, colorful blankets and clothing, and the noble woman standing in the saddle, gazing far into the distance.

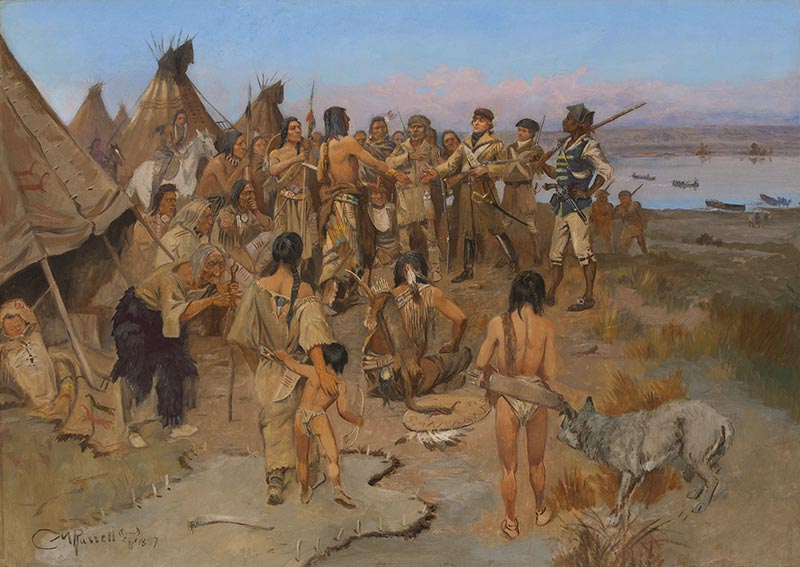

Captain William Clark of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Meeting with Indians of the Northwest, dated 1897, illustrates that even a more authentic chronicler of the West such as Russell can encounter problems with details. The Native American accoutrements in the painting, which should have reflected lifeways of the early 1800s, were instead those of a later period, the times when Russell himself would have witnessed them on the northern Plains.

Both artists lamented the end of the wild old days of the American frontier in bronze, on canvas and in literature. “The West is no longer the West of picturesque and stirring events,” Remington proclaimed in 1907. “Romance and adventure have been beaten down in the rush of civilization; the country west of the Mississippi has become hopelessly commercialized…The cowboy—the real thing, mark you—disappeared with the advent of the wire fence…”

While I still find the West to be pretty darn stirring and picturesque—and I imagine you do too—I’d still like to have seen it in the days of Remington and Russell. The Cowboy Artist’s primary theme was also “the West that has passed.” But as Dippie observes, Russell’s art more than Remington’s, “speaks with an almost mystical passion of lost love.”

“One can feel the alkali dust rising from the sunbaked earth,” wrote a St. Louis reporter of the Cowboy Artist’s work in 1910, “the dryness of the dead sage brush, and the refreshing green of the cacti growth, the grandeur of the distant mountains, and the light of the early morning sun…”

“When the nester turned the West grass side down,” Russell wrote to a friend in 1922, sharing habits of grammar and spelling with his good friend Will Rogers, “he buried the trails we traveled. But he could not wipe from our memory the life we loved. Man may lose a sweetheart, but he don’t forget her.”

One of these days I hope to complete a tour of museums and sites devoted to the Titans of Western Art. The Frederic Remington Museum in Ogdensburg, New York, features a comprehensive collection of his paintings, sketches and sculpture. The Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, includes a reconstruction of Remington’s studio, as well as artworks by both Remington and Russell. Other institutions with R&R collections include the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, the Gilcrease Museum of Tulsa and the Briscoe Western Art Museum of San Antonio. In Great Falls, Montana, the C. M. Russell Museum illuminates the world of the Cowboy Artist with exhibitions, programs and special events. On their website (https://cmrussell.org ) you can order a copy of the Montana PBS documentary film, C.M. Russell and the American West.