By Gene Fowler

New Exhibition Spotlights the Artist’s Love of the Cowboy Way

Andy wore cowboy boots. Who knew? Wait—what? Andy who? If you were alive for very long in the last century, you know this particular Andy only needs one name. Andy Warhol, the pop artist who held a mirror up to American culture, the late, inscrutable hipster-trickster of the avant-garde, liked to slither around Manhattan with his dogs encased in cowpoke couture.

Actually, of course, it’s really no surprise. Cowboy boots…I mean, what’s not to love? The archives at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, the artist’s hometown, preserve some 27 pairs of Andy’s boots. Half a dozen of ‘em have temporarily headed west to Oklahoma City, where you can admire them right now as part of the exhibition, Warhol and the West, at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum.

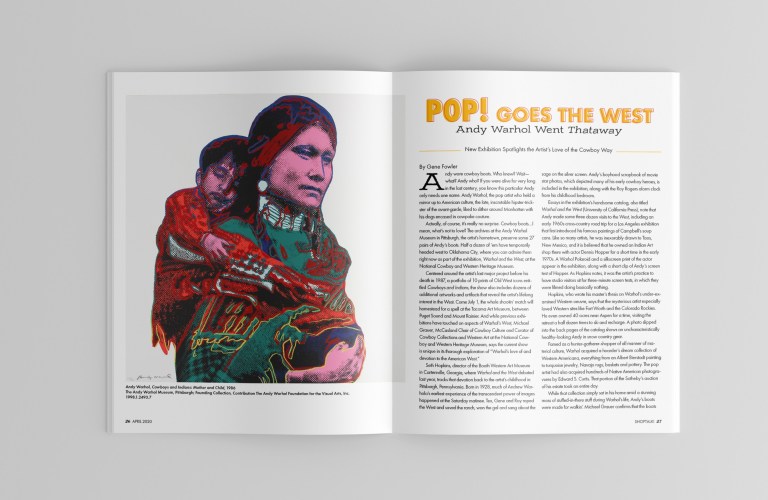

Centered around the artist’s last major project before his death in 1987, a portfolio of 10 prints of Old West icons entitled Cowboys and Indians, the show also includes dozens of additional artworks and artifacts that reveal the artist’s lifelong interest in the West. Come July 1, the whole shootin’ match will homestead for a spell at the Tacoma Art Museum, between Puget Sound and Mount Rainier. And while previous exhibitions have touched on aspects of Warhol’s West, Michael Grauer, McCasland Chair of Cowboy Culture and Curator of Cowboy Collections and Western Art at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, says the current show is unique in its thorough exploration of “Warhol’s love of and devotion to the American West.”

Seth Hopkins, director of the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, where Warhol and the West debuted last year, tracks that devotion back to the artist’s childhood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Born in 1928, much of Andrew Warhola’s earliest experience of the transcendent power of images happened at the Saturday matinee. Tex, Gene and Roy roped the West and saved the ranch, won the gal and sang about the sage on the silver screen. Andy’s boyhood scrapbook of movie star photos, which depicted many of his early cowboy heroes, is included in the exhibition, along with the Roy Rogers alarm clock from his childhood bedroom.

Essays in the exhibition’s handsome catalog, also titled Warhol and the West (University of California Press), note that Andy made some three dozen visits to the West, including an early 1960s cross-country road trip for a Los Angeles exhibition that first introduced his famous paintings of Campbell’s soup cans. Like so many artists, he was inexorably drawn to Taos, New Mexico, and it is believed that he owned an Indian Art shop there with actor Dennis Hopper for a short time in the early 1970s. A Warhol Polaroid and a silkscreen print of the actor appear in the exhibition, along with a short clip of Andy’s screen test of Hopper. As Hopkins notes, it was the artist’s practice to have studio visitors sit for three-minute screen tests, in which they were filmed doing basically nothing.

Hopkins, who wrote his master’s thesis on Warhol’s under-examined Western oeuvre, says that the mysterious artist especially loved Western sites like Fort Worth and the Colorado Rockies. He even owned 40 acres near Aspen for a time, visiting the retreat a half dozen times to ski and recharge. A photo slipped into the back pages of the catalog shows an uncharacteristically healthy-looking Andy in snow country gear.

Famed as a hunter-gatherer-shopper of all manner of material culture, Warhol acquired a hoarder’s dream collection of Western Americana, everything from an Albert Bierstadt painting to turquoise jewelry, Navajo rugs, baskets and pottery. The pop artist had also acquired hundreds of Native American photogravures by Edward S. Curtis. That portion of the Sotheby’s auction of his estate took an entire day.

While that collection simply sat in his home amid a stunning mass of stuffed-in-there stuff during Warhol’s life, Andy’s boots were made for walkin’. Michael Grauer confirms that the boots on display in Oklahoma City “are clearly well-worn” and that many bear ancient paint splatter, fragmentary evidence of the nearly constant production of the man some experts consider the premier American artist of the twentieth century. (Some of his boots, however, remain pristine and Seth Hopkins postulated in a recent interview with Mark Sublette, of Tucson’s Medicine Man Gallery, that Andy might have donned those beauties for hanging at Studio 54.)

Branding, in many ways, was creative oxygen for Andy Warhol. And the artist almost reinvented himself with a classic Western name. When creating his own artistic persona, he experimented with various names, eventually settling on his family name of Warhola minus the final “a.” But, he signed a 1954 drawing with the name Andrew Morningstar. “I always wanted to change [my name],” he wrote in a 1984 diary entry. “When I was little I was going to take ‘Morningstar,’ Andy Morningstar. I thought it was so beautiful. And I came so close to actually using it for my career.”

Crow Indians called General George Armstrong Custer, the Son of the Morning Star. Kent Klineman, the publisher of Warhol’s Cowboys and Indians suite, said that Andy was a “huge Custer fan” and insisted on including a print of Custer in the portfolio even though Klineman (rather uncharitably in our humble opinion) deemed the general “an idiot and an overused cliché.”

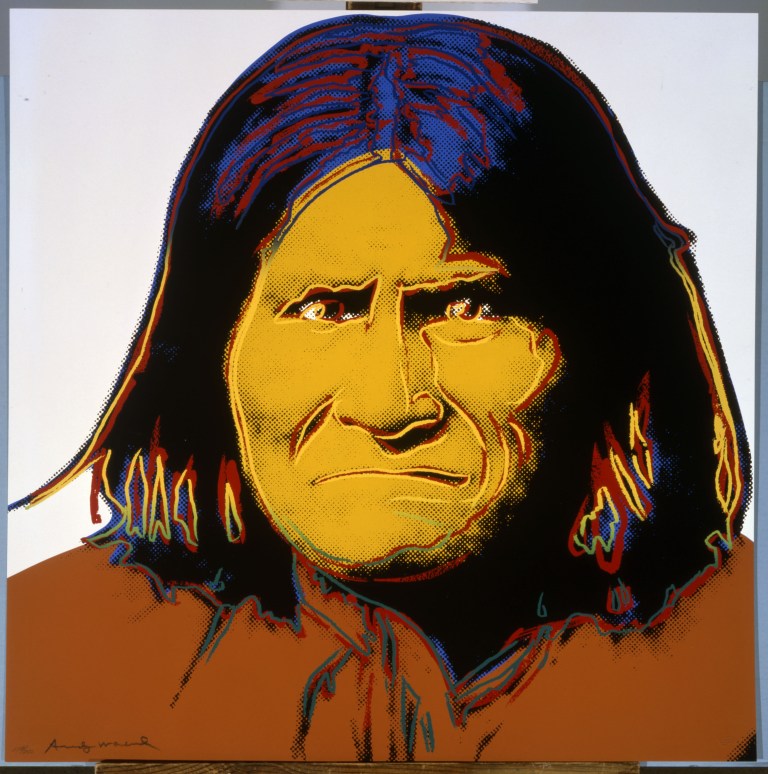

The Custer print was modeled on an 1865 photograph of Custer taken by Matthew Brady during the Civil War. While it is not at all uncommon for artists to base works on other created images, Warhol became something of an appropriation factory, turning out prints, paintings and other renderings of soup cans, Brillo boxes, ketchup packages, Coca-Colas, bananas, flowers, Micks, Marilyns, Jackies, Liz Taylors, Maos and Elvises by the thousands. His print of Geronimo in the Cowboys and Indians portfolio and in the exhibition is based on A. Frank Randall’s 1886 photograph of the Apache warrior and medicine man, one of the most photographed Americans of the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the heavily staged but still compelling photograph, Geronimo kneels, grasping a rifle with both hands and levels a gaze upon the camera lens at once wild, fierce and weary. Senior curator at the American Indian Cultural Center and Museum in Oklahoma City, heather atone (who intentionally declines to capitalize her name), contributes an illuminating catalog essay applying recent and developing perspectives on cultural appropriation, and assesses controversial elements of Warhol’s art practice in those contexts.

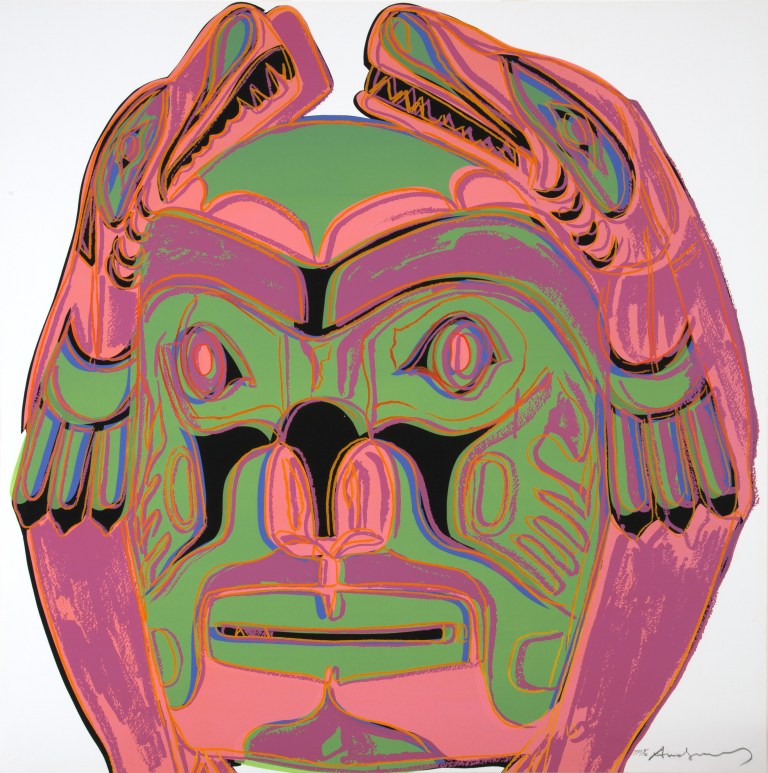

Other legendary and oft-mythologized figures in the Cowboys and Indians suite include John Wayne, Teddy Roosevelt and Annie Oakley. The portfolio also included an anonymous Native American woman and her child, the Indian Head nickel, a Plains Indian shield, Kachina dolls and a Northwest coast mask. Andy’s image of a pistol-raising Wayne is drawn from a poster for the 1962 John Ford film, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Warhol’s portraits of Sitting Bull in the show represent several pictures that were experimented with, but not included, in the final portfolio of 10 prints in 1986.

The prints of historical figures –each set against an empty white background and rendered semi-electric with their bold outlining and tasty application of rich color…sometimes muted, often vibrant– seem like they could be fugitive neon signs from ghost motels holed up in the Black Hills or spread along Route 66. They’re like glowing specters floating in the vast atmosphere of the Western edge, blinking, occasionally flashing brilliantly, to life.

Or as Faith Brower, Haub Curator of Western American Art at Tacoma Art Museum puts it, “Warhol took the familiar Western characters and made them pop,”…making “historical photographs modern through their appropriation and transformation….he instills them with renewed relevance.” Brower’s catalog essay profiles several contemporary Western artists influenced by Warhol, such as Frank Buffalo Hyde, Maura Allen, Billy Schenck and Duke Beardsley. The curator quotes Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s peppy maxim that contemporary Native American artists seek to “break the buckskin ceiling.”

Along with portraits of Dennis Hopper, additional prints and paintings in the show feature some of Andy’s artist friends from the West, including Georgia O’Keeffe, R. C. Gorman and Fritz Scholder. And while Warhol always contended that his work contained no agenda, his 1976 series of 38 paintings and 23 drawings entitled The American Indian (Russell Means), is interpreted by Paiute performance artist and painter Gregg Deal as “Warhol’s nod to Indigenous struggles and resistance.” The current exhibition contains at least two of the Means portraits.

Amongst the popster’s nods to art history in the show, museumgoers can see both his screen print Action Picture and the early 20th century oil painting that it’s based on, Charles Schreyvogel’s Breaking Through the Line. Both depict blue-coated soldiers riding hell-for-leather in a battle with Indian warriors.

Having grown up mesmerized by shoot-em-ups and, as Seth Hopkins theorizes, playing “cowboys and Indians” himself, it was only natural that Andy Warhol the filmmaker would turn his camera to the grand tradition of the horse opera, albeit in his singular Andy-fied style. The artist made two experimental Westerns, Horse in 1965 and Lonesome Cowboys in 1968. Carefully selected, g-rated looped footage from both films is included in Warhol and the West. For the first film, Andy brought a horse into his New York studio and the steed ended up kicking one of the actors in the head (a critical gesture some movie reviewers may have wished they could have performed). For Lonesome Cowboys, the experimental filmmakers invaded (and somewhat scandalized) the vintage Western film set of Old Tucson and the art community of Rancho Linda Vista in Oracle, Arizona.

“Warhol and the West is an opportunity to see an entirely new exhibition of art of the American West by one of the most recognized names in all of American and world art,” says curator Michael Grauer. “Andy Warhol is someone not usually associated with the American West, and this show is not to be missed.”

Backing up their assertion that the artist’s Western work has been overlooked, Grauer, Brower and Hopkins point out in a triple-authored catalog introduction that no prints from the portfolio Cowboys and Indians were included in either the 1989 Andy Warhol retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York or in the 2018 Whitney Museum of American Art Warhol retrospective, also in the Big Apple; nor are any regularly shown at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.

And while this exhibition enlightens us on the importance of the West in Warhol’s vast body of work, it also reminds viewers of the artist’s primary role in popularizing the screen print or serigraph in a fine-art context, as well as his huge influence on the art world in general. “There is no way,” art critic Dave Hickey, now in his late seventies, once expounded, “that anybody who is much younger than I am can understand how profoundly different the world before Andy and after Andy looked…He literally changed the way the world looked.” And even in the Great American West, that’s a big dang deal.

Warhol and the West Exhibitions

Each Show Unique

For any Warhol fans following the show across the country, as music fans once followed the Grateful Dead, be aware that subtle differences will occur at all three stops. “Neither of the Fritz Scholder original portraits were shown at the Booth Museum,” says Michael Grauer. “Both are at the National Cowboy Museum and will be exhibited at Tacoma. The Howdy Doody portrait was at the Booth, but is not at the National Cowboy Museum venue and I don’t think it will be in Tacoma. However, an original Howdy Doody cowboy marionette from the National Cowboy Museum’s permanent collection is shown at the National Cowboy Museum and will travel to Tacoma. The Edward S. Curtis original photogravures from the John Wayne Collection will be shown only at the National Cowboy Museum. Reproductions of the Curtis images were shown at the Booth and will be shown at Tacoma. The original plaster castings from James Earle Fraser’s Indian Head and Buffalo Nickel are shown at the National Cowboy Museum, as they are part of our permanent collection. These will not travel to Tacoma.”

This article originally appeared on Shoptalk Magazine and is published here with permission.

You can find the Andy Warhol Museum under the heading for Pennsylvania in our section on Museums.