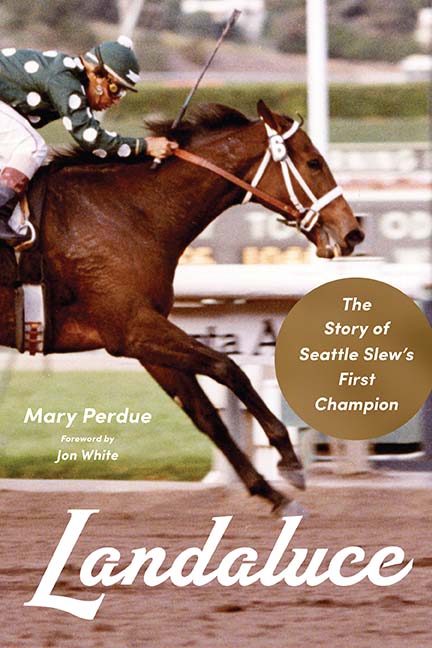

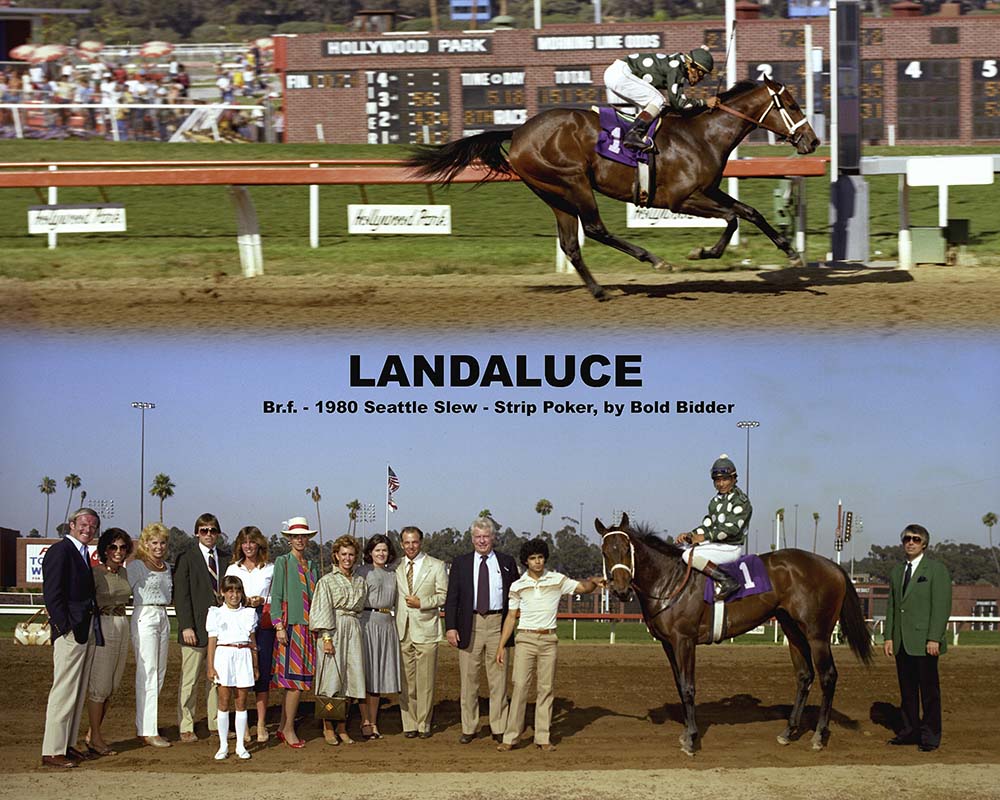

When Triple Crown winner Seattle Slew retired from racing in 1978 to stand at stud at Spendthrift Farm, no one could be certain he would be a successful sire. But just four years later, his dark bay daughter Landaluce won the Hollywood Lassie Stakes by twenty-one lengths―a margin of victory that remains the largest ever in any race by a two-year-old at Hollywood Park. California horse racing had a new superstar, and Slew was launched on a stud career that would make him one of the most influential sires in North America. Like her father, Landaluce soon became a national celebrity, and was poised to become the next American super-horse. But those dreams ended when the two-year-old died in her stall at Santa Anita four months later, the victim of a swift and mysterious illness. Today, with her "I Love Luce" bumper stickers long gone, the filly has been largely forgotten.

In Landaluce: The Story of Seattle Slew's First Champion, Mary Perdue tells the story of a horse whose short but meteoric career could have changed racing history forever. Sparking comparisons to Ruffian, Landaluce helped elevate California horse racing to the national stage and could have been the first filly to ever win the Triple Crown. In telling this story, Perdue explores the lives and careers of Landaluce's breeders, owners, and trainer, D. Wayne Lukas, as well as her famous sire Seattle Slew―and shows not only how one filly captured the imagination of racing fans across the country, but also set the stage for another filly turned super-horse, Zenyatta, in the decades to come.

Excerpt from "Landaluce: The Story of Seattle Slew's First Champion" by Mary Purdue

Good From the Beginning

“Young horses…are usually very green…, and then develop…but she was good from the beginning.” --Laffit Pincay

Thirty-two-year-old Laffit Pincay, top rider for the Wayne Lukas barn, made his way from the jockeys’ room to the paddock at Hollywood Park on the bright, sunny afternoon of Saturday July 3, after having hurriedly changed into Beal and French’s hunter green silks with white polka dots. Already among the top jockeys in U.S. racing history, and inducted into the National Racing Hall of Fame seven years ago , Laffit had more important things on his mind besides the upcoming race for maiden two year old fillies he was about to ride.

It was the middle of a big holiday weekend at Hollywood, with a crowd of nearly 34,000 on hand to enjoy some of the West Coast’s most important stakes races , including today’s feature, the Hollywood Express , in which Laffit would ride favorite Time To Explode against a field of ten of the circuit’s best older sprinters. Then there was the Hollywood Oaks on Sunday for three-year-old fillies, and the American Handicap on Monday. Laffit had top mounts in all of them. Wins in these races were vital for Laffit to wrest the meet’s riding title from younger jockey sensation and defending national champion Chris McCarron, who was ahead of him in total wins. Laffit’s ultimate goal was to surpass his idol Bill Shoemaker’s record of 8,883 lifetime wins, and he needed to be aboard winners every day to make that happen.

Laffit was having a spectacular summer, with the month of June an embarrassment of riches on both coasts: Just a few weeks before, after guiding Conquistador Cielo to a win over older horses in track record time in the Metropolitan Handicap at Belmont, he had finally broken his “Triple Crown drought” with a stunning fourteen- length victory aboard the bay son of Mr. Prospector in the Belmont Stakes for trainer Woody Stephens, following up with a victory on the sensational gelding Perrault in the Hollywood Gold Cup. But that wasn’t all: to top it off, he had ridden sprinter Time To Explode to a new world record in an allowance race right here at Hollywood for trainer Gary Jones. Among these wins, the Belmont was most satisfying, for after a decade of promising mounts in the classics, including a heartbreaking second-place finish on Sham behind Secretariat, Laffit had failed to win a Triple Crown race. Conquistador Cielo’s Belmont win proved once and for all that he could capture the classic races, erasing the lone blemish on his star-spangled career.

Still, Laffit was a perfectionist. Consumed with an overwhelming desire to be the best in the sport, he couldn’t afford to let up now. To stay ahead of McCarron and to catch Shoemaker, he needed to be on the best horses in each race, every day , and he needed to stay in peak physical condition. Laffit struggled throughout his career to keep his weight at or near 112 pounds , while remaining fit enough to power winners home through the stretch. His self-discipline with respect to diet and exercise even among a jockey colony obsessed with these rituals, was legendary. In a sport where the average rider’s career lasted only five years, Laffit’s had already spanned eighteen. For over half his life, he had secretly subsisted on a diet of less than 400 calories a day , while working out at the gym daily and visiting the sweatbox, once managing to lose six pounds in four hours. A typical diet for Laffit was coffee with a plain piece of toast every other day, nothing for lunch, and one ounce of boiled rice and two ounces of chicken or steak for dinner. He was once observed scraping salt off a single cracker before eating it. When winning owners invited him to dinner to celebrate, Laffit either politely declined, or went along and ate only three ounces of chicken while the rest of the table savored thick steaks and champagne. Wayne Lukas, whose filly he was about to ride, had been shocked on the way home from the races on a private plane with Laffit when dinner was served: as Wayne dug in to his meal, Laffit pulled a single peanut from his pocket, split it in two, and ate half.

Laffit had convinced himself such strict regimens were necessary to overcome an illogical but deeply-held belief that many of his colleagues were superior riders. “I never believed I was the best,” he said. “I always felt that a lot of these guys were better. I had to work harder and do more if I was going to compete with them.” In the 1970s, Laffit started jogging on the track in the late morning after horses had finished their workouts as another way to burn calories and remain fit. “I couldn’t work horses in the mornings because it took too much out of me,” Laffit admitted, opting to conserve his energy for the grueling race day ahead. He didn’t want anyone to know there were times when the stress of diet and weight loss left him feeling too weak to ride. He needed all his strength to push his mounts over the finish line in the last sixteenth of a race, a skill at which he excelled. Other jockeys laughed and shook their heads when they saw Laffit in these human morning workouts, but as he began to break earnings and win records, some started to join him.

Today, as Laffit approached the saddling enclosure before the fourth race, the mood at the track was festive. In the early 1980s, Hollywood Park was among the premier racing facilities in the U.S., attracting fields of top runners and attendance of 123,000 for this weekend alone, nearly 30,000 more patrons than Belmont Park, its nearest competitor. Saturday racegoers often arrived as early as 10 a.m. to grab a spot on the rail or to enjoy activities in the infield, including adult softball games and a playground for children. Buffets were set up in the infield, an orchestra played, and female patrons could get their hair and nails done at a beauty salon in the clubhouse, where fans might catch a glimpse of many celebrities regularly in attendance, including Cary Grant, Elizabeth Taylor, Joe Namath, Walter Matthau and Mel Brooks, who liked to bet long shots. On days like today, the track’s parking lot was so tightly packed that Marje Everett sometimes came out of her office to direct cars into stalls.

Laffit loved riding at Hollywood Park and had won more races here than anywhere else. He was in a good mood. He twirled his racing crop and smiled as he walked past the Hollywood Gold Cup memorial, inscribed with the names of winners of the track’s signature race, run since it opened in 1938 and won by Seabiscuit that year. Laffit had already won five times, most recently with Affirmed in 1979 and with Perrault just weeks ago.

The only thing was, he was overweight by one pound on the filly he was about to ride in this race for Wayne Lukas, and he was two pounds over on Time To Explode in the feature for Gary Jones. Laffit knew that both trainers had immense confidence in him, or they would have replaced him with another rider if they deemed the overages significant enough to affect their entry’s performance. Still, in spite of everything he’d done to make weight, Laffit couldn’t help wishing he was just two pounds lighter. To bring himself luck, Laffit wore his underwear inside out—a habit he’d employed since his first race in Panama as a teenager in 1964.

As he walked into stall number six where Wayne and assistant trainer Laura Cotter were preparing her for the first race of her life, Laffit saw the dark bay daughter of Seattle Slew for the first time. As is often the case with top jockeys , he had never worked or ridden her before---he was simply too busy. Wayne had wisely refrained from sharing the news that Laffit’s rival Angel Cordero had worked the filly a week ago , and was so impressed that he offered to surrender his New York mounts to ride her in this race. Laffit’s agent Tony Matos, who secured the mount, had told him that Wayne “was very high on this filly,” and Laffit had learned to trust Wayne’s opinion when it came to assessing his starters’ prospects . Still, Laffit, like most jockeys, rarely shared the degree of optimism felt by trainers , especially when it came to unraced two-year-olds. Green or inexperienced horses learning to break alertly from the gate, race in tight quarters, accelerate or wait until asked , and handle crowd noise and the excitement of live racing for the first time, were unpredictable at best and disastrous at worst. Laffit knew that with two-year-olds, anything could happen. It was best not to expect too much.

On the other hand, Laffit respected Wayne’s horsemanship , and knew he was developing a reputation for being particularly adept with fillies. Laffit had been riding for Wayne ever since he switched from quarter horses to thoroughbreds. When he won his first race for the trainer aboard three-year-old colt Current Concept, Wayne had joked, “I know he can run a quarter mile. After that, you are on your own.” Since then, Laffit had guided Wayne’s top horses Terlingua, Effervescing and Island Whirl, among others, to stakes victories during those early years. Although it slipped his mind today at Hollywood, Laffit had also ridden Landaluce’s half-brother Clout to a turf win for Wayne at Del Mar four years ago, when the colt first came to the Lukas barn from the East Coast.

Laffit noticed that the filly stood quietly in her saddling stall, seemingly unruffled by the crowd, and made no fuss when Wayne cinched her girth, or slipped her halter off over his trademark white bridle . He thought she had a nice air about her. All these were good signs.

As Laffit swung his leg up over the filly, and prepared to head to the post, Wayne predicted, “you’re really going to enjoy this…Just sit perfectly and she’ll run like a six-year-old.” But Laffit could not have anticipated what was in store for him. Neither he, Wayne nor any among the crowd in attendance knew that what was about to unfold in this seemingly ordinary maiden race would eclipse anything else at Hollywood Park that day.

You can find more interesting articles and stories in our section on Recreation & Lifestyle.