by Judith Martin Woodall

"In my opinion, from a physiological point of view, it would be immeasurably better for women to ride astride. This position, on horse[back] would, I think, render the exercise of much more benefit to women. The circulatory and muscular systems would receive the greater tonic effect from the riding in this symmetrical position.” Dr. Sarah A. French, M.D. 1

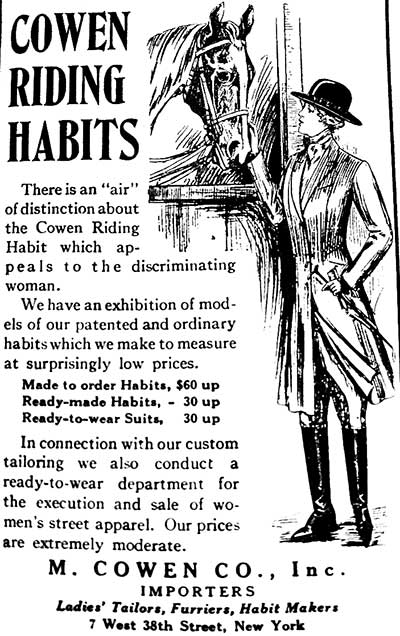

In 1895 most horsemen and women would have answered the question with an emphatic, NO! But Dr. French was among 500 physicians in New York City who responded to an inquiry from Ernst Carl von Gillmann, the head riding master at Dickel's Riding Academy on West Fifty-sixth Street in New York in January of that year. The issue had been roiling for some time and was given added attention later in the year when the British actress, Dorothy Chestie, was arrested on a charge of disturbing the peace while riding astride in Central Park. She was apprehended wearing a knee-length fitted coat that draped across her upper thigh and back over the cantle of the saddle. To complete her habit, she sported a bowler hat, a high-necked white shirt, light-colored bloomers tucked into tall boots, and dark gloves. The actress, who was appearing in the play, The Newest Woman, a comedy satirizing the growing feminism of the era, declared that she always wore bloomers, always rode astride at home in England, and was herself a “new woman.”

Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt was asked to “interpret police duties in such a case.” The Commissioner frequently rode in the park where he could be seen in a top hat and frock coat, the complete opposite of his now prevalent rough rider image. He issued a statement that there was no law against women riding astride, provided they were riding “in a proper manner.” 2 Based on existing photos, Chestie was not a polished rider, which may have been a factor in the mountie's decision to arrest her.

Gillmann confessed that he had never given much thought to women riding astride. The riding master found it difficult to obtain dispassionate views on the subject, especially regarding the female anatomy. It was an article of faith among naysayers that women could not ride astride safely because their cushioned derriéres prevented them from sitting deep in the saddle, and their legs from the hip to the knee were shorter and rounder than a man’s, making it difficult to "grip." Even if their thighs were not overly round, as "the weaker sex," they simply hadn't the strength to grip and needed the support of a sidesaddle. One horsewoman observed as late as 1912 that she might accept the "fraudulent notion" that women had insufficient gripping power if it were not for the numbers of men she saw falling off their horses in Central Park on a regular basis.

Anatomical issues paled in comparison to standards of aesthetics and propriety. Those "wide female hips" would not be shown to advantage in a cross saddle, and the very thought of a woman straddling a horse in full view of the general public was unseemly, to say the least. In a weak attempt to appear unbiased, some observers pointed out that heavyset men, like certain New Jersey riding club members known for their "ponderosity," did not look particularly attractive from behind either. On the other hand, a Mrs. Col. Morton of Roseville, New Jersey claimed to be the first "lady" to ride astride on the town's "beautiful suburban drives." She also declared that the sidesaddle "should be relegated to the archives of the past." 3

Gillmann, a teacher first and foremost, sought the opinions of medical doctors “in the interest of science and the enlightenment of women.” Since the early decades of the nineteenth century, it had been common for physicians to recommend riding for health to both men and women, and very few responses were negative. The medics believed that cross saddle riding would be far better exercise and would maintain women's internal organs in a more natural position, thereby giving the viscera the shaking up that many thought necessary to good health.

The Medical Record concurred but noted that the dictates of “fashion, custom and habit are infinitely stronger than that of reason, logic, and physiology.” 4

To their readers’ amusement (and shock), the journal suggested that there was a better argument, anatomically speaking, for men to ride sidesaddle. It would save them from the dreaded “Scythian disease,” a nineteenth century code for homosexuality and general feminization allegedly caused by atrophy of male sexual organs. The ancient Scythians, a mounted tribe of Central Asia, were said to be prone to all sorts of vices, a source of which may have been the pounding their testicles took from so much of life spent on horseback.

Sightings of women riding astride in the Central Park sometimes made the papers even before Chestie's arrest, but they were generally clad in long, split skirts. A young woman, described as "Spanish," – read, foreign – was spotted riding in the park with her husband. She wore a kilt-type skirt over "Turkish" trousers making it difficult to determine that she was astride, and if the wind caught her skirt while she was on foot, "nothing indelicate could be revealed." 5

A more sensational incident occurred when the variety hall performer, Lona Barrison, attempted to compete in the high school class at the National Horse Show in 1896. Officials went into a tizzy when they saw that her horse was tacked in a "man's saddle" and Barrison was wearing a frock coat over tights, the common undergarment of sidesaddle habits. Her entry was rejected, but The Rider and Driver, the national journal published in New York, was certain that horse show officials were not opposed to women riding astride, “provided that the bounds of decency were not transgressed.” Had she been willing to don a divided skirt, she would have appeared “modest enough,” and there would have been no problem, 6 but Barrison did not just wear any old tights. She wore "fleshlings," the flesh-colored tights that were part of her strip-tease act at the Winter Garden Theater – an act she had perfected at the Folies Bergère in Paris.

Barrison could have chosen from any number of classes at the National, but her horse, Maestoso, apparently governed her choice of the high school class. The horse may have been one of the first Lipizzans to come to America, and one of the Barrisons later claimed that the horse had been trained in the Spanish Riding School. Lona sued the NHSA for damages, but the suit and her attempt to ride in the horse show were seen as a publicity stunt and went nowhere.

Like so much else attached to the fashionable life in Europe and America, attractive equestrian attire was almost as important as riding skill. Dr. French favored astride riding both aesthetically and anatomically and was certain that "beautiful and picturesque costumes" could be devised. The president of the Ladies Riding Club of Chicago echoed the doctor when she declared that once that hurdle had been crossed, the sidesaddle would disappear “like snowflakes in the river.” Another physician, T. Gaillard Thomas, agreed with the science, but not the look. He was a member and later president of the exclusive Riding Club of New York where women could not ride astride from the front doors of the club well into the twentieth century. A club groom led the horse into the park where the rider mounted up.

The Rider and Driver saw itself as an upholder of equestrian and societal virtue, but conceded that women riding astride had caused no rents in the moral fabric of society. It did not stop the magazine from publishing a page of caricatures, "Costumes for the Park and Road," whose central figure bears a resemblance to the women's rights activist, Susan B. Anthony. The more fanciful costumes were designed for riding in the hunt, playing polo, astride a race horse, and serving in the cavalry, "bound to come in our time." The journal was not far off. All of those things came to pass, (excepting the horse cavalry), and with better attire. The desire for women to leave the confines of the bridle path and participate in more active horse sports was a powerful incentive to ride astride.

Manhattan in the 1880s and 1890s was blessed with several large riding schools in the vicinity of Central Park and all had men and women teachers on staff. The most prominent were Dickel's (1850-1901), Central Park Riding Academy (1876-1920), Durland Riding Academy (1887-1926) and the Riding Club of New York (1883-1936), known simply as "the" Riding Club. These facilities had indoor arenas measuring in the range of fifteen thousand to eighteen thousand square feet and accommodations for upwards of 300 horses.

Women and their children were crucial to the financial success of these establishments. They were regular participants in lessons and park riding as well as the shows, galas, and mounted games that carried the schools from autumn to spring. Rules forbidding women astride in and outside the schools and clubs remained in place into the twentieth century, but the importance of women's patronage eventually obliged the schools to accept the inevitable. This change was further hastened by a routine aspect of training. It was common for little girls to begin lessons astride and then graduate to the sidesaddle at around age eleven or twelve, but inevitably the youngsters did not choose to "graduate." In a further ironic twist, as "the weaker sex," women and girls were accustomed to more extensive riding instruction than men and boys – a fact that saw girls dominating the earliest equitation classes when horse shows finally began to offer them.

About the Author

Judith Martin Woodall is a Wisconsin native and long time resident of Manhattan. Her earliest riding experience was being turned loose at age four in a small pen on a Shetland pony (no hat, no restraints). She began her working life as a copywriter, and a chance encounter with some riders in Central Park led her to the Claremont Riding Academy, where she fulfilled a lifelong desire to learn to ride. She continued riding at Claremont on and off for a number of years. Not long after her publishing employer downsized in 1979, Paul Novograd, Claremont's proprietor, hired her to "help out." She worked as "the desk person", a/k/a all-purpose employee, a/k/a office manager, a position she held until 2007, or as she calls it, "the world's longest temporary job." Her love of horses and history prompted her to begin research into Manhattan's equestrian history for which she was awarded a John H. Daniels Fellowship from the National Sporting Library and Museum in Middleburg, Virginia in 2011. The result is the recently completed but as yet unpublished, 'Witching the World, A History of New York On Horseback'.

Book Synopsis

'Witching the World' begins in the eighteenth century with trick riders who went from town to town entertaining audiences with feats of horsemanship and teaching the noble art in their off hours. It ends with the closing of Manhattan's Claremont Riding Academy in 2007, arguably the oldest riding school in the United States at that time. The growing pains afflicting the city and the new republic in the early decades of the nineteenth century – concepts of universal education, better health, leisure pastimes, national defense, and the evolution of modern sports ¬– are reflected in equestrian history. Horse people were an influential part of the development of Central Park. Polo was introduced at Dickel's Riding Academy in 1876. The National Horse Show, the brainchild of New York horsemen in 1883, became the acme of the equestrian year and led to the birth of other institutions integral to equestrian sports in the United States. Throughout this long history, the riding clubs and schools provided a lens through which to view the changes, conflicts and attitudes regarding class and gender, war, fashion, animal rights, civil rights, and the art, science and evolution of horsemanship. It is a story of saints, sinners, romance, comedy, tragedy – in other words, the ordinary, the extraordinary, and the love of horses.

Find more interesting articles in our section on Recreation & Lifestyle and also in Books.

Adapted from 'Witching the World – A History of New York On Horseback' by Judith Martin Woodall, © 2020 by Judith M. Martin. All rights reserved.

1. Ernst Carl von Gillmann. Illustrated Lectures on Horsemanship, As Delivered at the Dickel Riding Academy, Season 1895. New York: H.B. Creagh, Publisher, 1895. 98.

2. "Women's Right To Ride Astride, 1, Part 1. The New York Times, August 31, 1895.

3. Gillmann, 100.

4. "Should Women Ride Horseback Astride," 209. The Medical Record. February 16, 1895.

5. "Ladies Riding Astride," 13. The Rider and Driver, May 2, 1891.

6. "Women Riding Astride At The Horse Show," 7. The Rider and Driver, November 28, 1896.