by Dr. Gerd Heuschmann

In this excerpt from his book Collection or Contortion? renowned veterinarian and advocate for the sport horse Dr. Gerd Heuschmann questions modern training methods that, while long known to be damaging to the horse’s body and mind, still find acceptance in arenas today.

Every rider dreams of having a horse that is easy to ride, supple, comfortable to sit on, elegant, and also meets the requirements of the preferred discipline. The horse should have a work ethic, be powerful and healthy, friendly, like to be with people, and be pleasant to get along with—in other words, a dream horse.

The fulfillment of this dream is largely in our hands. To achieve this, a long and very interesting path of development lies before us, and there will be many emotional moments along the way. There will be days of defeat and discouragement, but also many full of contentment and great joy!

The learning and development process of a rider takes many years, even decades, but finally puts him in the position to correctly train a horse. Over time, riding as many different horses as possible, as well as serious theoretical study, create an experienced, feeling rider. There are no young masters—even if you are considered a talented young rider!

The writings of the old equestrian masters of the eighteenth to twentieth centuries and the intellectual debates among authors such as François Robichon de la Guérinière, Alexis-François L’Hotte, Albert-Eugène-Édouard Decarpentry, Ludwig von Hünersdorf, Ernst Friedrich Seidler, Louis Seeger, Gustav Steinbrecht, Bernhard Hugo von Holleuffer, Oskar Maria Stensbeck, Gustav von Dreyhausen, Julius Walzer, Felix Bürkner, Hans von Heydebreck, Otto Lörke, and Richard Wätjen are, in my opinion, a necessary requirement if someone wants to really understand the classical principles of European riding culture.

During the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries up to our time, a training system was developed and documented arising from the experience of great and well-known leaders of the riding art.

This training system is appropriate for the horse’s nature, his body, and his mind. It fits his natural movements, as well as how he learns. This system provides guidelines that enable training of the horse to the highest level that is suitable for the horse.

The old masters recognized that an artificial, in the worst case, forced positioning of the head and the neck of the horse (as with Rollkur and hyperflexion), as well as artificial elevation (absolute elevation) always leads to stiffness in the horse.

This has been extensively tested, found to be useless, and is considered to be damaging to the horse’s health. In fact, early examples of such fundamental errors can be found in the texts and sketches of Paul Plinzner, James Fillis, and François Baucher.

Knowing this, isn’t it doubly questionable that now, in the twenty-first century, both concepts have been recently “discovered” and have quite a few supporters? The concept of classical dressage starts with a strong and dynamic hind leg that swings forward under the horse’s center of gravity.

The goal of dressage is to develop an athletic horse with powerful forward movement that follows the aids of his softly sitting rider with absolute “throughness.” It isn’t about a slave that dutifully does some nonsense with hovering, tense strides in a “sand box” (riding arena).

Nor does it have to do with a machine that can shine up our own ego in some big show. The true art of riding has neither money nor fame, nor even an exaggerated feeling of self-worth at the heart of it.

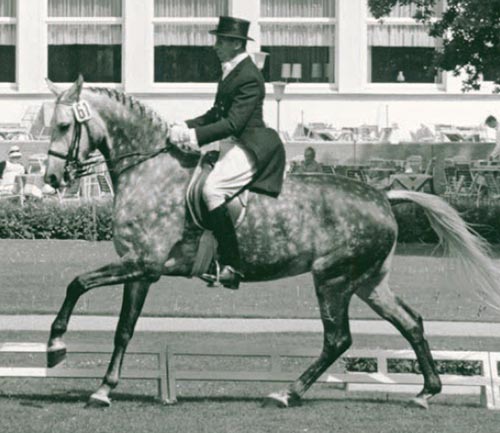

A Grand Prix dressage horse should be this relaxed

when riding outside of the arena.

It shouldn’t be impossible to control a highest-level, world-class dressage horse at an awards ceremony. He shouldn’t be bolting—accompanied by loud calls for help from the rider—and leaving the scene of his “questionable” triumph at a full gallop! And a dressage horse shouldn’t be so tense that at home in his own environment he can’t ride past a new flower pot or a dog running by!

All these experiences are a daily reality to which many people have become accustomed. The rider doesn’t respond to these experiences by considering what he is doing on the horse’s back—the horse is blamed for these behavioral issues.

All environmental stimuli must be removed so that the “dressage queens” can creep by the frightening spots and corners of the riding arena on a horse that is full of energy and stress. According to these people, “modern horse training” should take place in sterile, windowless, indoor arenas with white, soundproofed walls. I have personally seen two such riding arenas!

This undesirable trend has been recognized much too late, and many riders, especially in dressage, have a completely wrong picture of horse training. Every day in riding arenas around the world, extremely tense horses with the head pulled to the chest are whipped around the arena by an equally cramped rider.

This is not fair to the animal and doesn’t comport with our ethical principles. Riding a horse like this can’t give joy and is ultimately harmful for human and animal.

Why do we allow such riding? We shouldn’t measure our training efforts on the basis of competitive success. No, we should start a massive education and training campaign that gets accepted by all young professional riders. We must motivate riders to have a fundamental rethink.

At the top of the sport, change won’t be possible through education but through political resolution, especially for dressage (but also certainly true for other disciplines that I haven’t personally ridden, such as various Western disciplines, gaited horses, and others).

Waldemar Seunig wrote on this subject in 1981 in his book Meister der Reitkunst und ihre Wege (Masters of the riding art and their ways): “During the first 20 years of the twentieth century everything turned on its head including riding values.

Judging with a point system won international approval. As they killed what was living art and reduced the imponderable to ciphers, the competitors were reduced to marionettes in a game running circles on a drawing board.

Even Decarpentry had to use the FEI judges’ tables. But he always remained aware of the fact that reducing performance to a number hid the danger that the riding world would lose the sense of art. Whoever judges only by the points looks at the handwriting instead of the expression and misses the indivisible unity of content and form.”

This excerpt from Collection or Contortion? by Dr. Gerd Heuschmann is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.horseandriderbooks.com). Find out more about Equine Studies and training in our section on Clinicians & Trainers.