by Gene Fowler

Perched all pretty on the Colorado River, where the limestone hills of Central Texas tumble down from the west to meet the Blackland prairie from the east, the city of Austin has changed a lot since I first laid eyes on it in the 1960s.

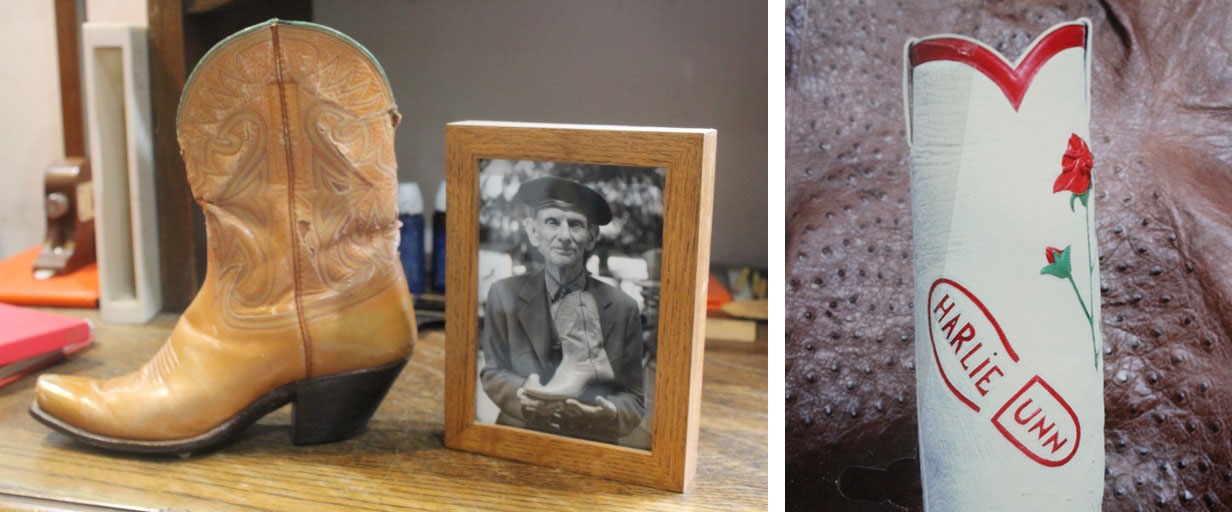

I’ll know for sure, though, that the place has devolved to high-tech heck if they ever take down the giant cowboy boot that has adorned a Lavaca Street building since….well, it seems like ever since Davy Crockett played his last fiddle tune at the Alamo back in 1836.

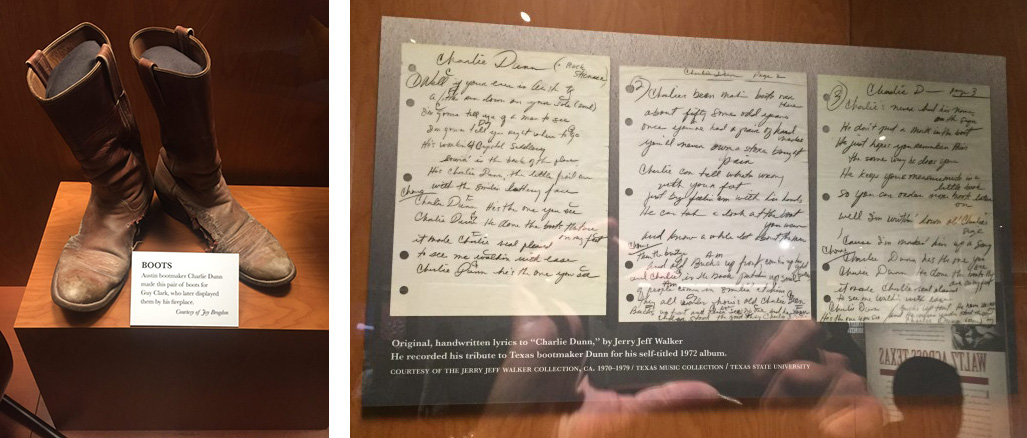

The boot once marked the Capitol Saddlery. Rodeo star Buck Steiner opened the boots-and-saddles emporium around 1930, and the legendary Charlie Dunn built boots for Buck from 1949 to 1974. Charlie’s bootmaking career at Capitol Saddlery and elsewhere spanned some 80 incredible years. Singer Jerry Jeff Walker made Dunn extra famous in 1972 with an eponymous ditty about the diminutive bootmaker “with the smilin’ leathery face.”

“Charlie Dunn,” Walker crooned. “He’s the one to see.” Thousands of satisfied boot wearers, many of whom surely treasure their custom Dunns today, 27 years after Charlie’s death, know that the song sang true.

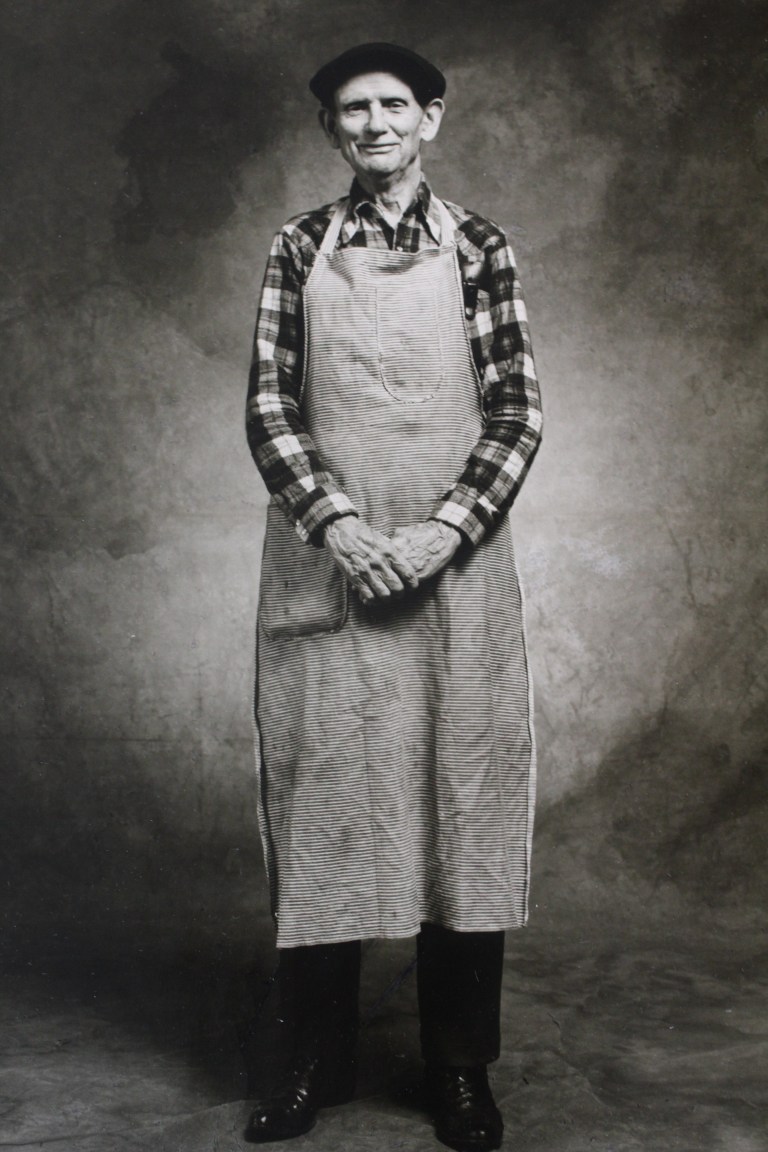

Folks who knew Charlie describe him as “leprechaun-like….mischievous….with a twinkle in his eye.” His former apprentice and bootmaking-heir-designate Lee Miller recalls that the beret-clad bootmaker “played the part of a Picasso.” Austin native Don Hyde, who first met Charlie in 1953 when Hyde was five years old, asked his dad “if Charlie was one of Santa’s elves.”

Charlie Dunn’s life unrolls like a heartland yarn spun by Mark Twain. Born on an Arkansas riverboat in 1898, he came from a long line of bootmakers that stretched back to his ancestors in Ireland. When Charlie was three, the Dunn family—which eventually included at least nine children—headed west by covered wagon. A new century filling the horizon before them, they settled for a time in the Texas hamlet of Glory, just south of the Red River and near the somewhat larger town of Paris.

At age seven, Charlie told hordes of reporters he became an apprentice in the Parisian shop of a one-legged bootmaker named Ed Lewis. Anxious to learn, the boy moved in with the Lewis family the following year. (Paris historians say that pre-1916 local newspaper archives were lost in a fire, but later clippings refer to one E. F. Lewis as the “Crippled Shoemaker.”) “He was a master himself,” Charlie said in 1974, “and in those days, they did like they did in the old country. You served your apprenticeship in the master’s shop, and you lived in his home, and you had to do housework and look after his children, babysit, and so on.” According to one account of his life, Charlie produced the first pair of boots made completely on his own as an 11th birthday present to himself.

The wandering Dunns departed Glory, Charlie in tow, and eventually landed in Fort Worth for about three years. In Cowtown, as the city was known, Charlie’s father opened Dunn Boots in the Stockyards District at the corner of Main and Exchange streets. In 1913 or so, the family loaded up another covered wagon and headed back across the Red River of the South, as Charlie always put it, “to escape the big city.”

The Dunns established a shop in Van Buren, Arkansas, and three of Charlie’s brothers also apprenticed in shoe and bootmaking, at least for a time. Charlie worked in the shop, but left home at age 15 after a falling-out with his stern father, whom Charlie also described as “quite a dude, a ladies’ man.” The adventurous teenager crossed the Arkansas River and found a job at the Henry Rose shoe shop in Fort Smith, about five miles from Van Buren, making four times the salary he’d earned at his father’s shop.

I located evidence of one Henry Rose of Fort Smith, who died in 1915. His obituary says he was connected for 30 years with the Arkansas Hide and Fur Company. But, nailing definitive places and dates to Charlie’s wanderings and hat-hangings can be tricky. Often, he did not tarry. As he explained to his granddaughter Linda Gann (now Linda Porter) for her 1977 college sociology report on aging, if he couldn’t learn anything from the people he worked for—or if they were instead actually learning from him—he’d work about a week and move on. “My intentions were to gain all the knowledge I could in the shortest time I could, in bootmaking, shoemaking, repair, in all allied leatherwork attached to that,” he explained. “I’ve never cared for anything other than bootmaking, shoemaking, repairing and fitting.”

He headed west to Lawton, Oklahoma, at some point, where he took a subcontract job repairing boots and shoes for Fort Sill, which Charlie recalled as quite lucrative. Taking a train back home to visit, he arrived with a case of smallpox apparently contracted from fellow passengers. His mother swathed him in carbolated Vaseline to treat the disease. Back on his feet, Charlie joined the Navy. At 112 pounds, he was told to guzzle three quarts of milk and gobble some bananas to pack on weight before his induction physical.

As the bootmaker recalled to his granddaughter, the First World War had just ended and he remained in the Navy about a year and a half before receiving an honorable discharge. A year of his service was spent aboard the USS Mayflower, Woodrow Wilson’s presidential yacht. Charlie did behold the commander-in-chief, though not on the yacht. “I saw him once sitting up in his box in a theatre,” he told his granddaughter. “Was some opry house. I remember who was up on stage, too. It was Will Rogers, doing his rope trick, with his cowboy uniform, boots and everything. President Wilson sitting up there like a vegetable. After he had that attack, he lost his mind.” (Dunn was likely referring to a stroke that President Wilson suffered in October 1919.)

Mustered out of the mariner life, Charlie found his way to Memphis, Tennessee. There, he met and married the love of his life, Cecile Tidwell, in 1921, and went to work for Joe Reese’s American Shoe Shop. The couple remained in Bluff City on the Mississippi throughout the Twenties, welcoming four offspring. As the Great Depression gripped the nation in 1931, Charlie moved Cecile and their three surviving children to Van Buren, where he opened a repair shop.

Times were hard and the shop failed. The bootmaker moved his family to San Antonio where, Charlie recollected in 1978, he found work at Kelly Field, altering boots for the Air Force. Then he made and repaired military and cowboy boots at Fort Sam Houston. “We were right inside the base,” he told his granddaughter. According to one account, the bootmaker first met Buck Steiner in San Antonio, as Buck had a contract to make saddles for the Army.

While working at Fort Sam, Charlie said, he made a pair of boots that won first place in their category at the Texas Centennial celebration held in Dallas in 1936. United States Vice President (and Texan) John Nance “Cactus Jack” Garner saw the boots at the Texas-sized birthday party and loved them, so the Army boot shop gave them to him when the exposition was over. Charlie noted that the boots were size 7 1/2, which happened to be Cactus Jack’s size. “I think he only wore them once,” Dunn recalled. “He said they were too pretty to wear and he put them up on the mantel.”

It appears that Charlie made boots at Mercer Boot Company in San Angelo, Texas, at some point in that same year, 1936, when another legendary Texas bootmaker, M. L. Leddy, bought out Mercer. Leddy opened his own San Angelo boot shop, which is still in business today. One of Leddy’s bootmaking grandsons, Rusty Franklin, recalls the family story that Charlie Dunn and several other storied, independent-minded Texas bootmakers left the shop after Leddy took it over and instituted his “my way or the highway” code to the art of making boots. And Kyle Brock, current owner and bootmaker at a revived Mercer Boots, confirms that the shop archives used to include photographic evidence and other material about Charlie’s time in San Angelo (the material disappeared with a departing employee).

By 1939, Dunn had moved to Austin, where he went to work repairing footwear for Lone Star Shoe Service. After he’d been with the company a few years, they discovered he could make boots, and that’s when his reputation as “the Michelangelo of cowboy boots” really began. In town for a performance, rising honky-tonk star Ernest Tubb happened by the shop one day and spotted a pair of boots Charlie had made displayed in the window.

The boots sported what became the signature Charlie Dunn inlay, beautifully rendered roses. They fit the composer of “Walkin’ the Floor Over You,” and Tubb bought them. Admired on the feet of the popular singer, the boots eventually led other country-western artists, such as the colorfully attired Porter Wagoner, to Charlie’s work bench. And from 1949 to 1974, that bench was parked at Capitol Saddlery.

As the bootmaker recalled the story for his granddaughter, Buck ran a help wanted ad for six months, turning down other applicants, waiting for Charlie to answer it. “I heard you had kind of a temper,” Buck said when Charlie finally called. “I knew sooner or later you’d blow up, and when you did, you’d come right on out here.”

Buck was pretty much a smokin’ pistola his own self. Growing up in nearby Bastrop and then Austin, he quit school around third grade to work as a cowboy. At age 12, he left home to travel and perform in Wild West shows and rodeos. His specialty became riding bulls backwards, which paid mucho better than riding them forwards. At 16, he was back in Texas working for the San Antonio stockyards. According to the Texas State Historical Association’s brief biography of Buck, a law enforcement career was cut short when he shot at a carload of politicians while working traffic management during a parade.

Back in Austin, where a German immigrant ancestor had reportedly owned the town’s first harness and saddlery shop, Buck bought and sold land, operated his own touring rodeos and rented his stock to other rodeos, and managed his Capitol Saddlery. News reports say that Buck had as many as 96 saddlemakers working for him when the company built custom saddles and supplied ready-made saddles to Montgomery Ward and Sears and Roebuck. Son Tommy Steiner ran the rodeo business until closing it in 1984, and grandson Bobby Steiner won the world’s championship in bull riding in 1973.

Buck and Charlie maintained an ornery coexistence the entire quarter century that the bootmaker worked for Capitol Saddlery. U. A. Hyde, the father of Don Hyde (who said as a child that Charlie looked like Santa’s elves) also worked for Buck Steiner at Capitol Saddlery, doing publicity for the rodeos that Buck promoted with his son Tommy. Young Don had the run of the three-story building, which had been built in 1890 (or the early 1900s, according to another source) as a firehouse. “It was an amazing wonderland of a place for a kid,” he recalls, “with floor after floor of every kind of leather you could imagine.”

Don, who cofounded the first of Austin’s counterculture music venues, the Vulcan Gas Company, in 1967, explains that he has one A QUAD foot-type and had his boots custom-Dunn-made starting at age 15. His girlfriend used Charlie’s sewing machines and made him pants and a vest with leather she bought from Buck. “He made her a pair of boots with roses on them in 1968,” Don recalls. “He said that people used to go for fancy boots like that all the time, but hers were the first roses he’d put on boots in 20 years.”

Currently living in Italy, Hyde was surprised not long ago when ordering bespoke shoes from Stefano Bemer to find that the famed Florentine shoemaker was quite familiar with the legendary Texan Charlie Dunn.

After 25 years of making untold numbers of custom boots and—apparently—blowing a gasket at Buck on a regular basis, Charlie asked the old backwards bull rider for a modest raise. Refused on the raise, he quit, retired and moved to Mesquite, Texas, to be near his daughter. And then the boot world went a little nuts.

“Night and day,” he told one reporter, “they’d call me up from all over the country—even at midnight—sayin’ they couldn’t get a fit like they could when I was working.” Two Austin friends and customers—physician Dr. Don Counts and businessman Steve Wiener—were especially concerned that Charlie’s knowledge and skills might be lost to history. “I drove up to Mesquite to see him,” Dr. Counts recalls, “and he was bored and depressed, sitting with a box full of newspaper and magazine stories about his boots.” Counts and Wiener made the bootmaker a deal he couldn’t refuse.

The pair of boot whisperers set Charlie up in business back in Austin, with a free residence that came with a boot shop out back, free medical care and three times his Capitol Saddlery salary. The new shop, Texas Traditions, opened on June 23, 1977. The very first customer was the actor Peter Fonda, who was in town working on the film Outlaw Blues.

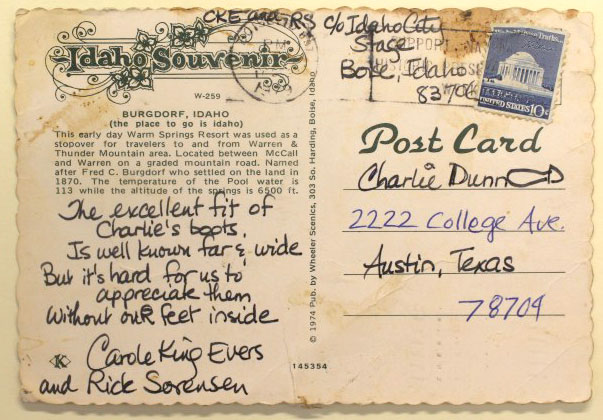

Resurrected before it had a chance to die, the Legend of Charlie Dunn soared. Boot lovers—the famous and the not-famous—found their way to Texas Traditions just off South Congress Avenue. Rosanne Cash wore Charlie Dunn boots on the cover of her 1987 album, King’s Record Shop. Carole King was photographed with Charlie by Jim McGuire, whose Nashville portraits graced innumerable album covers and spawned books and traveling exhibits. Standing next to the gracious singer-songwriter, the aging bootmaker looked full of impish glee.

Musing on his custom boot clientele, Charlie once allowed, “Musicians are pretty easy to suit. Rodeo riders want a boot that’ll practically fall off their feet if their feet need to leave the stirrups. Ranch hands want rugged boots with broad toes and no high heels. Ranchers and oil men want something like no one else has.”

One former rodeo athlete customer, who produced “buffalo rodeos” after he got to old to ride, was Hackberry Johnson. Having lost a leg as a young man, Johnson got his unique moniker when a doctor or some cowboys (depending on which version one accepts) fashioned a prosthesis from a hackberry tree branch. Hackberry died at a 1979 Willie Nelson concert, shortly after Charlie made him a new pair of boots. Nelson dedicated a performance of “Milk Cow Blues” to Hackberry, during which the 91-year-old cowboy cut the mustard with the ladies. When he collapsed a couple songs later, Hackberry died with his boots on.

Wheeler-dealer attorneys, football players, politicians, regular folks and the avant-garde also wore custom Dunns. Dr. Don Counts recalls that corporate bigwigs occasionally dispatched a private jet to fly the bootmaker to distant states to measure them for boots. “He first came to Texas in a covered wagon,” marvels the physician, “and he left many times in a private jet.”

No matter how high the muckety-muck, however, Charlie was seldom if ever intimidated. His granddaughter Linda Porter recalls the time that Little Pa (her name for Charlie) made a pair of boots for Idaho Governor John Evans. “My ex-husband worked for Governor Evans,” she explains, “so we brought Little Pa to Idaho to do a fitting. He was his usual odd self, telling the governor that he hoped he put on clean socks that morning. Lordy, Lordy.”

Dr. Counts says an artist from San Antonio kept changing the design and other details of his ostrich and calfskin boot order with Texas Traditions. “When the boots were finally ready and he came to pick them up, he apologized to Charlie for all the changes. Charlie just looked at him and said, ‘Well, I’m sorry I ever met you.’”

Apprenticeship was a big part of Texas Traditions’ mission. It was important to Counts and Wiener that Charlie pass his knowledge along to a younger generation, that the art and craft of handmade boots continue. “We sought out valedictorians of the Okmulgee [Oklahoma] School of Boot and Saddle Making,” Counts explains. “But, Charlie had a heck of a temper and his explosions would drive people away.”

Okmulgee graduate Lee Miller—who had heard the Jerry Jeff Walker song back home in Vermont and decided he wanted to make boots—had the gumption to stick it out and weather Charlie Dunn’s cantankerous style, as did Lee’s wife, Carrlyn, whom he met when she came to work at Texas Traditions.

“When I started working with Charlie,” Lee explains, “I felt like I was starting over. The minute I first walked in and saw how he did things, mixing Old World techniques with things he’d learned from Mexican bootmakers….the caliber of work really excited me.”

Dr. Counts recalls the way Charlie aligned the axis of the leather with the axis of the foot. Such an alignment not only aided the motion of walking, but it also added to the longevity of the boot. “And he drove square pegs into round holes on the sole,” Counts added. “He pounded a 10 penny nail flat on an anvil attached to an oak stump and that strengthened the arch and heel.” Along with other gizmos and machines Dunn used, the anvil on the stump is still at Texas Traditions today and still in use.

For Charlie, it was all about the fit, and that started with the last. A 1980 Texas Homes magazine account provides a vivid eyewitness description of his measuring technique. “When he approaches the fitting of a customer,” wrote the unnamed scribe, “Dunn is full of flourish and mystery. Beetling his brow beneath a cocked beret, biting a pencil, circling and circling the stockinged feet as if he had never seen anything quite like them during waking hours, he mutters an unbroken pattern of personal remarks, foot philosophy and foot humor: ‘Just stand naturally,’ he orders. He begins by tracing the outline of the foot. Then gently, so the customer doesn’t quite know he’s doing it, he takes her by the elbow and moves her off balance, coaxing her out of a posed stance, watching intently to see how her foot changes, sketching around it quickly and delicately. ‘There are some things I do that I won’t even talk about because I don’t want other bootmakers to know how it’s done. In my opinion, the foot is the most abused part of the human body. There’s no part of the foot that’s not important. You have to know just how each blood vessel crosses each bone.’”

All who beheld Charlie making boots marveled at his knowledge of the properties of various leathers. Dr. Counts recalled that if Charlie received 10 hides, he would keep one and send nine back, rejecting them as unsatisfactory. The excellent Wikipedia entry on Dunn, written by former UT professor Richard Ribb, includes a ribald rule Charlie applied to hides.

No detail was too small. He described the production of his own thread for granddaughter Linda Porter: “It’s polished flax. I do it by hand and use Russian hog bristles. They sell for 50 and 60 dollars a pound. I work it with my fingers and my knee. I wind the thread on my thumb and also use my thumb to twist it.”

Steve Wiener produced a 1983 DVD of Charlie detailing his bootmaking methods. Available from Texas Traditions, the video includes Lee Miller and other apprentices in action, and Jerry Jeff warbles his musical tribute to the man dubbed the “Michelangelo of cowboy boots” by Travel and Leisure magazine.

Charlie Dunn customers revered the artist’s handmade creations. When I visited Texas Traditions, Lee Miller showed me a pair of boots that Charlie had made for a California man. He was terminally ill and was returning the boots to Texas Traditions because he felt that’s where they belonged. “It reminded me of the journey in the film The Trip to Bountiful,” said Lee. “It was very moving.”

Charlie retired for good on his 88th birthday. Finally finding the time to watch the river flow and drop in a line from his fishing pole, he lived to the grand old age of 95. He was buried in his favorite pair of black kangaroo boots with rows of multicolored stitching that Lee Miller had made him in 1991. Before he died, Lee says, Charlie and Buck buried the hatchet. Buck lingered in this world until he’d seen 101 spins around the sun.

“I guaran-damn-tee you, Charlie Dunn was the best bootmaker who ever lived,” Steve Wiener told the Austin American-Statesman after Charlie’s passing. “He was a master craftsman, as well as a very artistic and creative guy. Everybody who met him walked out of that boot shop on a cloud of air.”

As the bootmaker’s mortal remains were returned to the earth, his grandson Don Rountree and Lee Miller sang, “Charlie Dunn, he’s the one to see….”

This article originally appeared in ShopTalk! magazine and is published here with permission. You can find ShopTalk! magazine in our section on Periodicals.

Read other interesting stories in our sections on Tack & Farm and Recreation & Lifestyle.