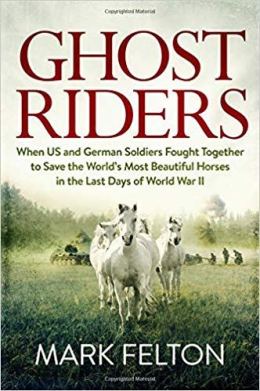

by Mark Felton

“The efforts to rescue the Lipizzaners would end with battle-weary American GIs standing shoulder-to-shoulder with German troops to fight a common enemy – the Waffen-SS.”

IT WAS APRIL 28, 1945.The war in Europe was just days away from ending when one of the strangest episodes of the entire conflict played out along the German-Czechoslovakian border. More than 350 American GIs had just fought their way through enemy lines to reach the town of Hostau.

The settlement, which was still in the hands of a detachment of Wehrmacht soldiers, was home to some remarkably valuable treasure: several hundred prized Lipizzaner horses. The famous and extremely rare animals, which had been seized by the Third Reich as part of a bizarre wartime livestock breeding program, were now in the path of the advancing Red Army where they faced almost certain destruction.

Fearing for the horses’ lives, the German officer in charge of the stud farm sent word to the Americans that he and his men would surrender en masse if the U.S. Army promised to get the beasts out of harm’s way. A cavalry unit in Patton’s Third Army leapt at the chance to save the legendary Lipizzaners.

The mission, which was dubbed Operation Cowboy, would see U.S. troops, along with a motley collection of liberated Allied POWs, a bona fide Cossack aristocrat and a platoon of turn-coat German soldiers race the clock to drive a herd of priceless horses to safety, all the while fighting off attacks by a legion of crack troops from the Waffen-SS bent on their destruction.

This unbelievable true-story was the inspiration for "Ghost Riders," a new non-fiction book by author and historian Mark Felton. Here, Felton himself takes us through the story.

When the shooting died away the snowy field was littered with dead and dying Waffen-SS soldiers. American GIs quickly reloaded their weapons.

Huddled inside their positions with them was a strange group of comrades. German Wehrmacht soldiers cradled Mauser rifles, while fur-hatted Russian Cossacks grinned fiercely through their beards as British and Polish ex-POWs stared grimly ahead. Leading this curious coalition that found itself in action near the Czechoslovakian town of Hostau was a tall, strikingly handsome U.S. Army captain by the name of Thomas M. Stewart.

Gripping his Thompson sub-machine gun, Stewart, already a grizzled veteran at the age of 29, scanned the field warily. The first SS attack had been beaten back, but the enemy would return. He glanced at his men. All had done well. ‘Stewart’s Foreign Legion,’ as they jokingly were calling themselves, had fought its first battle and won. Surrounded deep inside hostile territory, the small force was tasked with baby-sitting the world’s most precious horses. It was the toughest assignment Stewart had faced since landing in Normandy the previous year, but his most important. What was at stake was nothing less the survival than a living European treasure.

The white Lipizzaner horses of the famed Spanish Riding School in Vienna are world-renowned. Among the purest bred and finest trained show horses in existence, they boast an unbroken lineage that stretches back more than 400 years through the Hapsburg Dynasty. But all this was threatened with destruction in 1945, and the efforts to rescue the Lipizzaners would end with battle-weary American GIs standing shoulder-to-shoulder with German troops to fight a common enemy – the Waffen-SS. The action at Hostau stands as one of only two documented occasions when U.S. and German forces fought together against a common enemy during the Second World War. The other would take place days later at Austria’s Schloss Itter castle. (Check out MHN’s coverage of that incident HERE.)

After the German annexation of Austria in 1938, the Spanish Riding School’s breeding mares were taken by the Nazis to a special stud farm at Hostau in Czechoslovakia. The performing stallions stayed in Vienna. The mares became the focal point of a bizarre Third Reich breeding programme to try and create an ‘Aryan horse,’ along with Arabians and thoroughbred racing horses. Fast-forward to April 1945. The mares were still at Hostau and the war was drawing to its bloody close.

Twenty miles west of the city was General George Patton’s U.S. Third Army, drawn up along the Czech-German border. Having fought ferociously across Western Europe, the Third as was waiting for orders to liberate Prague. Forty miles east of Hostau sat the Red Army, poised to draw the whole of Czechoslovakia into Moscow’s political orbit as stipulated by the recent Yalta Conference.

Inevitably, the Germans in Hostau would have to surrender the Americans or the Soviets; everyone knew which option was the preferred one.

Meanwhile, the Wehrmacht veterinary officers charged with caring for the horses were growing ever more frantic. They feared that if the Red Army arrived first, the precious animals would be lost. The Soviets had already destroyed the Royal Hungarian Lipizzaner collection. Having shot many of the stunning horses rather than take care of them, the rest were forced into harnesses like common drays.

The ranking German at the farm was a Luftwaffe intelligence officer named Colonel Holters. His unit had become stranded in the area after running out of fuel. The waylaid oberst befriended the commander of the farm, a colonel named Rudofsky. The two men shared a passion for horses and Holters soon convinced Rudofsky to surrender his collection of prized steeds along with his men to the Americans before it was too late. Rudofsky vacillated, mindful of his oath to the Fatherland to resist. But Holters had no such compunctions and secretly set out to negotiate the surrender of the horses to the Americans on his own.

The unit that Holters approached was the 42nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, part of the 2nd Cavalry Group, the eyes and ears of Patton’s XII Corps on the border. A good proportion of the 2nd Cav’s officers were themselves horsemen, including the unit’s resourceful commander, Colonel Charles M. Reed, a polo-playing Virginian gentleman old enough to have served in the horsed cavalry before the rise of mechanized warfare.

Holters laid the groundwork for the surrender. A veterinarian from the stud farm was persuaded to cross the lines under a flag of truce to work out the complicated and risky logistics of moving several hundred priceless horses safely through the middle of a shooting war. Word of the plan was sent back to the German commandant who reluctantly agreed to the move. Reed was delighted and contacted Patton, who gave the go-ahead to snatch the horses.

But the problems were acute. Though the Germans agreed that the stud at Hostau was to be turned over to the Americans, the frontier defenses were not a part of the scheme and would resist any incursion by U.S. forces into Czechoslovakia. Then there were the men of the 42nd Cavalry: all were worn out after nine months of bloody slaughter from Normandy, the Ardennes and through Germany, and none wanted to be the last GI killed in Europe. To top things off, many of the horses were pregnant, while others had only just given birth.

Mindful that the Red Army was only days, perhaps hours, away, Patton ordered his men to carry out the mission and ‘make it quick.’ He couldn’t spare enough men and resources to ensure that the operation was a success – it would have to be performed on a military shoestring. The CO of the 42nd was ordered to provide two small cavalry reconnaissance troops and some armour for a 20-mile push into German-occupied territory. The task force commander, Major Andrews, was given just 325 men to enter an area defended by tens of thousands of German troops, including two understrength yet still potent Panzer divisions. Apart from the two troops’ machine-gun-armed jeeps and M8 armoured cars, the only other support Reed could count on would come from five small M-24 Chaffee light tanks, far outclassed by the German Panthers known to be operating in the area, along with a pair of Howitzer Motor Carriages, artillery guns mounted on light tank chassis. It wasn’t much of an army, but it would have to do.

On April 28, Task Force Andrews, as it was codenamed, set off amid an artillery barrage that blasted a hole in the forward German defenses. The advance was contested at virtually every village, but by a miracle the column reached the stud farm. Now came the difficult part – holding on to the prize.

While Colonel Reed sought out vehicles to move the pregnant mares and new-born foals out of Hostau to Bavaria, Andrews turned over the task force to his deputy, Captain Thomas M. Stewart. The force was reduced to one cavalry troop, two tanks and two howitzer motor carriages, a total of only 180 men. Stewart now faced the greatest challenge of his military career. Without enough men to secure the stud farm, the town of Hostau and the road back to U.S. lines, he’d need to recruit some extra manpower fast. He turned to a small group of Allied POWs who had been liberated alongside the horses. The Germans had been using the prisoners, a mixed bag of British, New Zealanders, French, Poles and Serbs, as labourers. All eagerly volunteered to help out and were immediately handed captured German weapons. But it still wasn’t enough. Next, Stewart turned to some anti-communist Russian Cossacks in the area. Commanded by a haughty former prince, the Cossacks joined the Axis after the Nazi invasion of the U.S.S.R. four years earlier. Eager to slip away from the encroaching Red Army, Prince Amassow and his excellent horsemen volunteered and were re-armed. Still coming up short, Stewart asked the German colonel Rudofsky for some of his own men to join in the defence. Stewart agreed to re-arm them if they pledged to serve under U.S. authority. Many were happy to do so; they had no love for the Nazis and all feared the arrival of the Soviets.

Using their own surrendered weapons and coal-scuttle helmets, the Wehrmacht volunteers fell in with their new allies. Stewart knew that he had had to act quickly in forming this unlikely ‘foreign legion’ for word arrived that SS troops were converging on Hostau determined to kill or capture the Americans and the horses.

In two battles, ‘Stewart’s Foreign Legion,’ with the assistance from the light armour, managed to hold off an assault by crack troops from SS-Regiment Deutschland. Several Americans were killed or injured in the firefight; more than 100 enemy soldiers perished, with an equal number of wounded. Fortunately for Stewart and his men, the Nazis lacked tanks, otherwise it would have been game over for the entire expedition.

During a break in the action, Colonel Reed began to organize transport to get the horses out of Hostau to U.S. lines. Many of the stallions were ridden out by American, German and Cossack officers, while some of the mares were driven on the hoof like some Wild West-style roundup. The others with their foals were loaded onto hastily converted German and American trucks and sent west.

The group made good its escape without a moment to spare; Soviet T-34 tanks arrived on the eastern edge of Hostau just as the Lipizzaners and Stewart’s Foreign Legion rolled out of town. A tense stand-off followed, but the Red Army decided not to risk a clash with Reed’s forces and Operation Cowboy was successfully completed with not a moment to lose.

(Image source: WhiteHouse.gov)

The Lipizzaners were eventually returned to the Spanish Riding School, where their descendants perform to this day. Colonel Reed would later sum up the entire operation: “We just wanted to do something beautiful.” And what could be more beautiful in the midst of the cruellest of wars than rescuing innocent white Lipizzaner horses for the betterment of European culture? But it wouldn’t have been successful without Captain Stewart’s foreign legion, who set aside national enmities for a higher reason and succeeded.

Mark Felton is the author of Ghost Riders: When U.S. and German Soldiers Fought Together to Save the World’s Most Beautiful Horses in the Last Days of World War II.

BUY NOW on AMAZON "Ghost Riders" - Kindle | Hardcover | Audiobook

A well-known historian and the author of 20 books, including international bestsellers Zero Night, The Sea Devils, and Castle of the Eagles, Felton regularly contributes to periodicals and often appears as a historical expert on television specials for Discovery, History Channel, PBS, Quest, and American Heroes Channel. He lives in England.

This article originally appeared on Military History Now and is published here with permission.

Find other interesting articles in our section on Recreation & Lifestyle.