Timing is everything. Nowhere is this more relevant than when preparing an elite equine athlete for a race.

Thoroughbred trainers are critically aware of the importance of fine-tuning the feeding and exercise regimes of their charges in the months, weeks and days before a big event. Timing is also critical for the smooth functioning of a horse’s musculo-skeletal system for optimal performance.

Understanding how the horse’s muscle physiology works in synchrony with its environment and reacts to the exercise regimes that we subject it to in our daily management has been the focus of much research at University College Dublin by Dr. Barbara Murphy and her team.

All animals possess an internal body clock that ensures functions such as muscle metabolism, digestion and tissue regeneration and repair peak at the most suitable time of day to ensure survival in the wild. This important system, called the circadian system, uses the continuous 24-hour transitions from night to day to generate rhythms in physiology and behavior that allow a horse to stay in harmony with its environment.

Each organ in the horse’s body undergoes rhythmical 24-hour changes that respond to the environmental cues provided by the changing light-dark cycle, food availability and exercise. How we time feeding, and in particular, exercise, has important implications for equine performance and will be explored here.

Domestication has changed many aspects of a horse’s daily life. To understand the impact human intervention has had on the horse’s body clock we must first consider their natural behavior. As migrating herd animals bound by tight social bonds, horses evolved to spend up to 18 hours a day grazing as a group constantly on the move, covering anywhere from 40 -100 km in a day.

Now consider the lifestyle of today’s thoroughbreds in training – stabled for up to 23 hours a day, isolated from a herd, fed concentrated feed at set intervals and often only exercised once per day at the same time each day. Each of these factors is accompanied by impacts on a horse’s health and performance.

Gastric ulcers, respiratory disorders and stereotypic behaviors are some of the common challenges faced by trainers and are often a direct consequence of an intensive indoor management regime – a necessary evil in the business of training elite athletes.

Research

So what impact does a regimental early morning training time have on a horse’s performance? To answer this, a recently published study from University College Dublin evaluated the effect of routine morning exercise on muscle response in thoroughbreds.

For the study, researchers chose six healthy four-year-old thoroughbred mares that had not been on exercise programmes previously. In the preceding year the mares had lived a sedentary life as a herd in a large pasture. The study horses were weighed weekly and only received a minimal grain enticement to encourage them to come in from the paddock each morning. They were returned to their paddock following exercise each day and remained outside at night.

At the initiation of the study, mid-gluteal muscle biopsies were collected from each horse at four-hour intervals over a 24-hour period. Researchers analyzed the samples for muscle genes that had previously been seen to undergo circadian (24 hour) oscillation in other species, or that were shown to have high importance for muscle metabolism in performance horses.

The horses were then put on an eight-week exercise regimen, which involved a 30-60 minute workout conducted on an automated 20 m diameter exerciser at 10.30 am each day, six days per week. In this way, all six horses could be exercised simultaneously in order to mimic a string of horses heading to the gallops at the same time each morning.

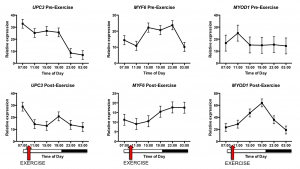

The intensity of exercise gradually increased each week, with speeds up to 12 km/h eventually maintained for up to 30 minutes. At the end of the study period researchers again took biopsies from each horse every four hours over a 24-hour period. Horses were not exercised on the day that samples were collected. Gene expression patterns in these samples were then compared to the patterns identified at the beginning of the study.

The data showed that prior to beginning the exercise programme, muscle genes were expressed constantly at a low level across the 24 – hour period. This fits with our understanding of horses maintained in a natural setting, grazing for most of the night and day while constantly moving. At the end of the exercise programme however, a distinct pattern could be detected in muscle gene expression for specific genes.

The shifts in the pattern of the genes matched their functions, so that genes involved in regeneration and repair were turned on at night and genes whose protein products help protect muscle against stress were turned on just prior to the 10.30 am exercise. This is an anticipatory effect regulated by the horse’s body clock and synchronized by exercise in order to provide optimal performance at the anticipated time of highest activity.

Bear in mind that this shift in muscle gene expression occurred in response to a medium intensity daily workout consisting only of walk and trot. A far greater response would be expected when horses are in intense training consisting of high-intensity fast work in preparation for racing and where the horses spend the remainder of the day confined with minimal activity in their stables.

After the first week of exercise all the horses lost weight. This was followed by six weeks of gradual weight gain. The initial weight loss was associated with a loss of body fat while thereafter an increase in muscle mass occurred as the horses adapted to exercise and became fitter.

Every stable hand is aware of the anticipatory response to feeding time in a barn of horses by the sounds of nickering and hooves scraping in impatience. This is a response to the circadian rhythm of enzyme release from the digestive tract in anticipation of food breakdown when feeding times are restricted to certain specific hours of the day.

While we cannot hear the horses’ muscles gearing up for exercise in the early morning hours, the same thing is happening and now we have molecular evidence.

One of the genes that was found to be turned on in a rhythmic pattern in anticipation of exercise was Uncoupling Protein 3 (UPC3).

UCP3 acts as an antioxidant defence mechanism to protect against damaging reactive oxygen species that are generated during exercise in skeletal muscle. Because exercise-induced oxidative stress is linked with a reduction in muscle performance and muscle damage, the implications are that in order to reduce the risk of musculo-skeletal injury, strenuous exercise should be scheduled at the same time as the horses daily training regime.

Of course, most race times do not coincide with when we routinely train horses.

Two genes with important roles in the growth and development of new muscle fibres, a process termed myogenesis and hypertrophy respectively, and whose patterns changed dramatically in response to the exercise regime were Myogenic Differentiation 1 (MYOD1) and Myogenic Factor 6 (MYF6).

Both of these genes showed a shift in the time of day of highest activation towards the evening hours, suggesting that muscle regeneration and repair functions occur in the evening in response to a morning training regime.

The take home message from this study is that the time of day of exercise influences the 24-hour activities within muscle tissue in the horse. Muscle proteins responsible for protecting fibres from damage are present primarily at the time of day that coincides with when exercise is expected, whereas the muscle building and repair functions are primarily carried out at the opposite time of the day to exercise.

So the question that must be asked is what is the consequence of asking an athlete to undergo strenuous exercise at a time outside of the daily training time? Furthermore, if muscle performance is sub-optimal outside the daily exercise time, is this true also of the cardio-respiratory system? These questions remain to be answered and are worthy of further studies.

Changes in patterns of equine gluteal muscle gene expression in response to a morning exercise programme. Horses underwent an eight week medium intensity exercise programme at 10.30 AM each morning. The red arrow indicates time of exercise. The white and black bars indicate daytime and nighttime respectively.

Conclusion

What is clear however is that the shorter and faster the work, the more important it is that it is carried out at a time that matches the competition time. Longer training periods, such as those associated with endurance work, will have a less important peak time for optimal performance. Training time is of highest relevance for horses who are restricted to minimal activity within a stable for all but one hour of the day – that hour then becomes the time cue for optimal muscle performance.

The saying goes that “all knowledge is worth having” and while it is very unlikely that many of us can shift training times from the early morning hours to the afternoon in order to facilitate optimum muscle performance on the track, trainers can still make use of this information to benefit their training regimes.

Alternating training times for horses between the first and last string has the potential to buffer against a peak in gene expression so that the benefits are spread over a longer time period. Additionally, the incorporation of an afternoon hack or ‘pick of grass’ is accepted by many as beneficial to the horse’s mental well-being, but now could also help with preventing an early peak in muscle metabolism.

Ideally, fast work should be scheduled at the time of day closest to actual race time as possible. This means that to ensure horses have the best opportunity to perform optimally and reduce the risk of musculo-skeletal breakdowns, training times need to be shifted to later in the day so that they coincide with racetimes.

At least we may now know the reason why some horses shine at home on the gallops, but fail to perform to their potential on race day.

See Equilume featured in our Farm Equipment section.

Are you interested in promoting your business or sharing content on EIE? Contact us at info@equineinfoexchange.com