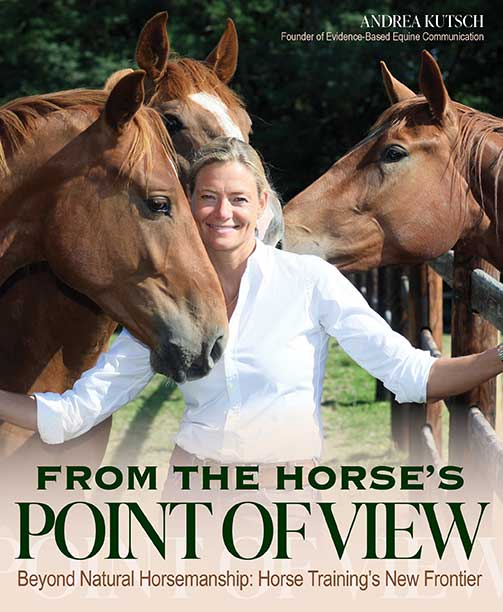

By Andrea Kutsch

The problem with most horsemanship instruction is that the reader can interpret the written word in many ways. In addition, every person who is involved with horses interprets horse behavior in a different way, according to the person’s own experiences. It is, therefore, very important that we agree on a “common denominator” and accept something that has been scientifically examined and proven: Horses fundamentally do not mean us any harm.

The equine nervous system processes signals that affect the horse incredibly quickly, especially on an emotional level. The human nervous system tends to act more on a strategic, planning level. Horses need to act quickly to ensure their survival. One wrong decision can have fatal consequences. When confronted with an external stimulus, horses have to decide whether to leave the situation—take flight—or to stay and wait to see what happens, focus, and attack if necessary. They have the option of driving away the stimulus or the person influencing their behavior.

Emotionally relevant external stimuli that have an effect on the horse have been scientifically proven to also have a major direct influence on the release of hormones controlled by the brain. These hormones then have a lasting impact on how the horse will behave in similar situations in the future.

For example, if being loaded into a trailer makes a horse nervous, there is an emotional reaction that causes stress hormones to be released. The process of hormone regulation generates a learning experience in the horse’s emotional brain, which can then be responsible for the horse’s future defensive behavioral responses. Examples of these behavioral responses could be a spook when just being led past a trailer, even if the human has no intention of loading the horse. The moment the horse sees the trailer, his brain makes a decision that triggers the behavior. This behavior often then provokes a lack of understanding in people, perhaps because our focus is somewhere completely different, so we often miss the important initial physical expressions of the horse’s anxiety. When we keep our human perspective, we might feel the horse is being unreasonable if he suddenly leaps or dances around us, snorting nervously as we try to pass the trailer as quickly as possible. We may blame the horse and punish him with a jerk on the rope, a shout, or a smack. This sets in motion a mutual spiral of anxiety because the horse’s emotional brain misses nothing.

We humans often find it difficult to shift our internal perspective to the horse and to see the world from his point of view, especially in moments that we initially thought were safe. When a horse suddenly exhibits a defensive behavior for reasons we can’t understand, we must learn not to accuse him of “being bad,” but to instead understand that his is a nervous, hormonal reaction rather than a cognitive behavioral response.

Horses can’t see ghosts, but they can see or perceive things that we miss. This sympathetic basic understanding helps us to respond empathically to the horse’s behavior. Instead of getting angry, we can decide to begin a training process that has a positive effect on the horse and that covers different experiences, without causing further stress that will make our life together increasingly difficult in the long term.

Horses have absolutely no interest in acting against us or planning things that could harm us. The structure of their brain doesn’t even allow them to process such complex interrelationships. From our perspective, we often think that horses deliberately don’t do things: “He doesn’t want to go for a ride because he’s lazy,” or “He snaps at me when I tighten the girth because he doesn’t want to be ridden,” or, “He knows that he can get away with it,” or, “He’s ignoring the aids because he can’t be bothered to do a flying change.”

These are human trains of thought. From the horse’s point of view, these scenarios are far less complex: “I canter and she kicks me in the ribs.” The horse probably isn’t ignoring the aids but instead doesn’t know that he’s supposed to do a flying change. He can’t think it through strategically. Only when the horse is able to understand the triggering stimulus—in this case, the backward movement of the rider’s leg that is supposed to precede the flying change—and that the flying change itself is associated it with this stimulus, will he then be able to put it into practice.

This excerpt from From the Horse’s Point of View by Andrea Kutsch is reprinted with permission from Trafalgar Square Books (www.horseandriderbooks.com).

You can find all kinds of interesting reading in our section on Books.