by William G. Gotimer, Jr.

Betting on horses has been a favorite pastime for centuries in many places around the world. Despite changes in almost every facet of life - betting on horses has remained largely the same. Determining the order of finish in a race of spirited horses has always been the pursuit. What has changed over the years is the mechanics of placing a wager.

Younger race fans have grown up with numerous ways to place a bet; multi-bet teller windows, self-service machines, telephone bets, internet wagering, wagering aps on phones – all modern methods.

Most people are even aware of the old fashion bookmaker models highlighted in shows such as Peaky Blinders where bets are transmitted through a series of calls, hand signals and chalk boards (hence the term “chalk” for a race favorite). But what about the period between the chalk period and the computer period?

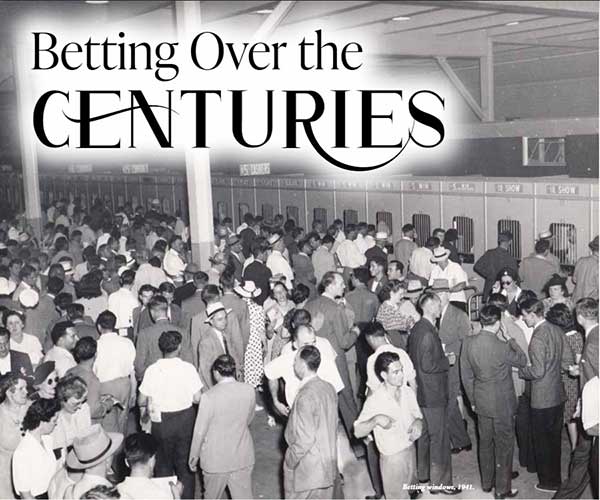

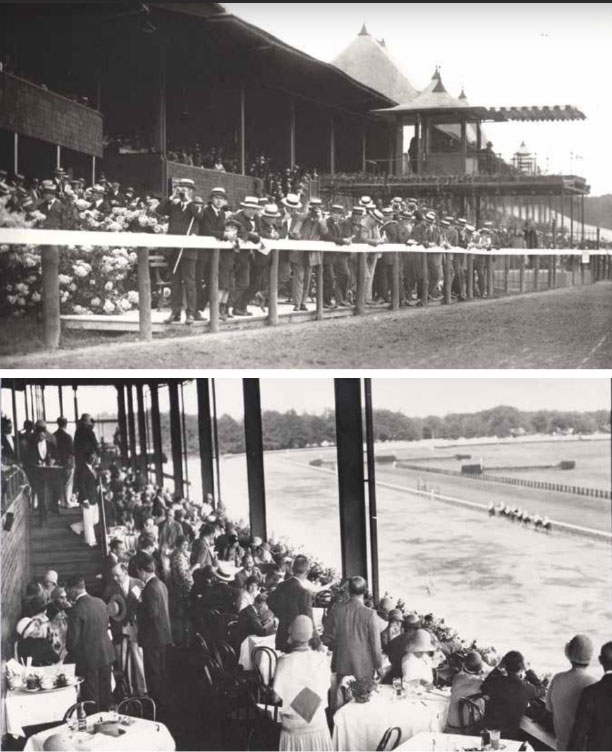

Not many remember placing bets in those days from the mid-1930s to the mid-1970s but placing bets required some determination. It was not for the faint hearted.

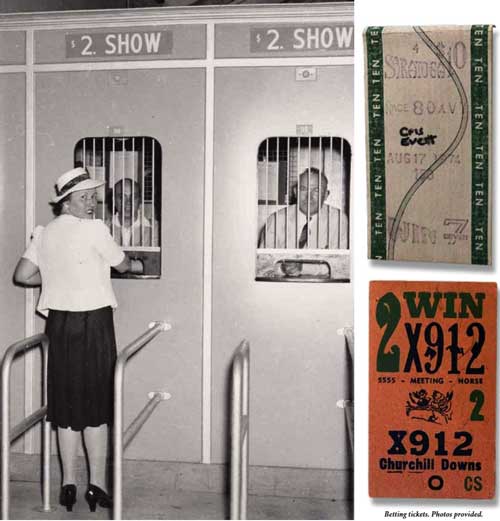

Much of the routine was driven by technological limitation. Placing bets and cashing bets needed to be done at separate windows and in fact were done on separate sides of the building. Placing bets was done on the windows facing the racetrack while cashing was done around the back facing away from the track.

A bettor having a losing day without cashing a ticket was said to “never make it the other side”. Winners could be seen rounding the corner to cash tickets while losers remained in place on the front side. Cashing tickets was done manually as was the math needed to determine your return.

Bettors needed to know exactly how much they were due lest an “error” intentional or accidental saw them leave some of their winnings behind at the window.

Both betting and cashing were segregated by amount and bet type with each machine capable of only selling one type of ticket. Originally each window only sold one type of ticket e.g. $2 Win tickets, later they could sell different types of the same denomination.

A $6 Combo ticket was $2 Win, Place and Show. Exotic bets such as exactas, doubles and triples were sold at separate windows meaning if you wished to bet a horse to Win and an Exacta in the same race you needed to stand on TWO lines.

This meant learning how to handicap “on line” not “online” – folding the Racing Form just right so you could stand in line and view past performances was a learned skill. Time between races was needed for standing in line – if you wanted a hot dog or beer you had to hurry – or “gasp” skip a race (which no one wanted to do because there was no simulcasting from other tracks and only the live races to wager on).

The tickets produced were of sturdy cardboard and contained the race number, number of the horse, denomination and bet type. Each ticket also had the pre-cursor to the modern “password” with a random listing of four or five letters that would confirm to cashiers that the ticket was from the proper day and race lest someone try to cash counterfeits.

In the vernacular of the day, a counterfeit ticket that was in fact cashed was referred to a “pigeon” or bad bird, and the amount erroneously disbursed was deducted directly from the cashier’s salary.

Each denomination was a different color meaning a fistful of losing tickets which were torn up resembled confetti (and was about as valuable). The term “tearing tickets” or “it’s better than tearing them up” came from the difficulty in tearing up the sturdy cardboard losing tickets.

After each race the floor was littered with losing tickets while bettors quickly moved on to the next race.

It different slightly at different tracks but in New York the only “exotic” bet was the double and it was only offered once a day – hence the term “Daily Double”. It was offered on races one and two at special windows. Later a “Late Double” was added making the original term Daily Double (still used on Jeopardy) a bit non-sensical.

When exactas were added, the limitation on machines led to exacta wagering being offered only on races three, five and seven. There were no such things as a “box ticket” but a sharp mutuel clerk knew how to quickly enter the six combinations in a three-horse box or the twelve combinations in a four-horse box. With a less talented clerk the bettor had to call out each separate combination.

When triple betting was introduced, it was offered on only on the last race of the day. It was viewed as a gimmick that allowed a last-ditch effort at “getting out” from a losing day. Tickets were sold at separate windows.

Unlike other bets which could ONLY be placed on a race-by-race basis, the triple bet was complicated, so windows opened two races before the triple race to give bettors time.

With long lines and limited time between races bettors had little tolerance for someone who got to the front of the line and dithered through fumbled words, indecision, or ready cash. A knowledgeable line of bettors could move quickly since everyone was prepared but one novice could stop the line to a crawl.

Veteran bettors made sure a novice make the mistake twice through loud, strong, and pointed criticism. (To this day I order food at a delicatessen with precision and speed lest I be yelled at by people behind me in line – it’s a discipline I wish others had learned.)

For modern bettors who view the above as medieval times consider this additional fact – THERE WERE NO ATMs – anywhere. That meant coming to Saratoga from downstate for a weekend of racing (particularly when Sunday racing was added) required, great discipline, a large amount of cash or friends who could lend you money.

As I said it wasn’t for the faint hearted but it developed life skills and habits that lasted a lifetime.

About the Author

William G. Gotimer, Jr. is an attorney and corporate executive with a practice in Saratoga Springs, New York. He has participated in thoroughbred racing in various capacities for half a century and advises many in the racing community on legal and business matters.

Mr. Gotimer’s credentials include a B.S. in accounting and Juris Doctorate from St. John’s University and an LL.M. in Taxation from New York University School of Law. He is available on a consulting or retainer basis. He may be reached at wgotimer@verizon.net

This article originally appeared in the Equicurian magazine and is published here with permission.

There are more interesting articles in our section on Horse Racing.

Are you interested in promoting your business or sharing content on EIE? Contact us at info@equineinfoexchange.com