Breed Profile: The Akhal-Teke

Courtesy of The Akhal-Teke Association of America

A horse like a shimmering gold mirage, its head held high, almond eyes focused on you, poised to leap into action, yet held by the tether of its deep bond with the human beside it.

That is the quintessential Akhal-Teke, a race that has shared its history with humans for thousands of years and is among the oldest equine breeds.

ORIGINS

These horses are descendants of the steeds that enabled the Scythians to dominate Central Asia until the 4th century BC, described by the Greek historian Herodotus as controlling a vast empire from the Russian Steppes and India westward to the Baltic and the Caspian Sea, The Scythians were partly pastoral, partly nomadic raiders who supplied slaves to the Greeks. Fast horses were essential to their trade.

It is claimed the Ice Maiden of the Altai Mountains, discovered 11 years ago and widely publicized in America through the Nova special, was a Scythian. This woman, who lived over 24 centuries ago, according to radio-carbon dating, was buried with six horses in gilt harness.

Her tribe has been called the Pazyryks. They occupied the mountain plateaus that now lie on the border between Russia and China. The Ice Maiden must have been a powerful figure to merit the sacrifice of so many horses, although in fact 5 were geldings and the sole mare was found to have crippling arthritis in her joints.

The horses were fitted with elaborate wooden saddles covered in felt, elaborately ornamented bridles with jointed snaffle bits, and antler-like headdresses. The “Ice Maiden” – so called because it was the permafrost that now covers this area that preserved her so well, was covered with tattoos, as was a man in another burial site.

Some scholars claim that the horses buried with her were prototypical Akhal-Tekes, as they quite unlike the Mongolian type horses that now populate the region and which is seen in Scythian artifacts as a pack animal. The riding horses are notably lighter, taller, and more refined, without the thick, lowset neck of the Mongolian horse.

The “golden horse” comes in black as well, and it has have suggested that black Bucephalus, the famous steed of Alexander the Great, was an Akhal-Teke. The breed is known for sometimes forming strong bonds with a single rider and rejecting all others. Bucephalus was famous for only allowing Alexander to ride him.

However, many of these claims are mixed with a strong draughts of nationalistic pride, and are as yet far from proven. Perhaps as the equine genome is further studied, more can be said on this subject. That the Akhal-Teke has an ancient lineage is beyond question, although it has borne many names over the years, from the “Celestial Horse” recorded in Chinese writings, to the Nissean, as it is called by Herodotus to Turkmene, to the Argamak as it was called in Russia.

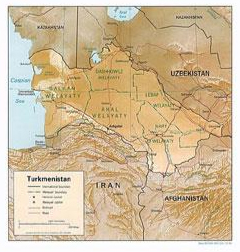

It is certain that the Akhal-Teke has retained much of its ancient character due to the geographic isolation of what is now considered its homeland, the Karakum desert of Turkmenistan. With Iran to the South, Afghanistan to the East, and the Caspian Sea to the West, this land was not always a desert.

Climate study has shown that at one time, it was a rich pasture land fed by waters from melting glaciers, but over the years the area became a desert and life there was shaped largely by the resource it lacked – water.

Those animals that survived had to travel great distances to find this precious resource. Speed and endurance were critical qualities. Human occupants of the region relied on their animals to survive, and also adopted a nomadic life to deal with the widely varying temperatures and rainfall.

Like the Scythians, the Teke people were raiders. Their tactics not only enriched them, they drove off those who might otherwise intrude on territory and use up precious resources. So the speed and superiority of the Teke’s horses were critical to their survival, and were given great importance in their culture.

The Turkoman horse was widely prized and exported throughout the region. Europeans brought them back from the crusades, and it is thought that many of the progenitors of the Thoroughbred, such as foundation sire The Byerley Turk and influential horses like Darcy’s White Turk and Darcy’s Yellow Turk (yellow being the eighteenth-century term for palomino) were in fact Akhal-Tekes.

If you read training manuals for racehorses of that time, it is clear that much of the racing culture was also imported from Turkenistan, such as the practice of heavily blanketing and “sweating” the horses to bring them down to racing weight.

Although the region was conquered many times and tribute extracted by different rulers, life there did not change greatly until the imperialist expansion of the nineteenth century.

The Karakum was just part of the buffer zone between regions dominated by the Russians to the North and the British to the south. In 1888 Russia annexed Turkmenistan, and altered the future of the Akhal-Teke horse.

The golden horses had long been favorites of the Russians, under the name Argamaks, and many of the Russian breeds such as the Don, show influence of Teke blood. The new name, Akhal-Teke, given to them by the Russians symbolized their origins at the same time as their bloodlines were appropriated.

An official stud was founded near Ashkabat, the best breeding stock collected and a stud book put in place. These horses were prized as cavalry mounts by the Russian military. But as imperialism was replace by communism, the Akhal-Teke suffered.

Collectivization of the farms crushed the nomadic traditions of living with the horses, and no individual breeding efforts were allowed. Motorcycles were tethered outside of yurts instead of horses, and the Akhal-Teke dwindled in it own birthland,

The traditional methods of training for the races, the wrappings of woolen blankets, the metal-plated bands that decorated the neck of prized horses, the careful feeding and endurance conditioning – all these were in danger of being lost, as the older generations who retained the oral traditions passed from the scene.

The role of the horse in social customs, like the ceremonial races held to celebrate weddings, was vanishing.

In the late twenties, a group of Russian scientists who were Akhal-Teke enthusiasts organized a new breeding farm, and sent horses to Kazakastan. The famous Ashkabat to Moscow endurance race, in which the pureblood Akhal-Tekes clearly demonstrated their superiority to Thoroughbreds and crossbreeds over great distances.

Akhal-Teke races were held in Russia and Soviet riders began to appear with Akhal-Tekes at international competitions, including the famous Absent, ridden by Sergey Filatov, gold medalist in dressage at the 1960 Olympics and winner of five other medals.

Without the intervention of the Russian enthusiasts, it is unlikely this breed would have gained worldwide attention. German breeders were among the first to begin to seriously try to establish their own stud farms, and in the late 70’s Phil and Margot Case brought the first Akhal-Tekes to the U.S., including the stallion Senetir, who was born in Ashkabat.

MODERN DISTRIBUTION

Now there are Tekes from Sweden to Australia, and two breeders right here in Washington State, as well as the Nez Perce breeding program, an experiment that aimed to return the Appaloosa to more of its original form by crosses with 4 Akhal-Teke stallions. Other popular choices for cross-breeding include Arab and Mustang mares.

Because of their relatively small numbers, Akhal-Tekes tend to be shown by their owners and breeders in North America rather than professionals in international competition. They are becoming increasingly popular as eventing and endurance mounts.

In its homeland, the Akhal-Teke has also experienced a renaissance, as it was elevated to a symbol of national pride. For more on this story, read about Geldy Kyarisov and how his passion for these horses finally landed him in jail in May’s feature article.

This native horse now races in Turkmenistan at a modern stadium, or hippodrome named after the recently deceased president who built it. Here the horses receive veterinary care of a quality not available to much of the human population of Turkmenistan.

But in spite of their increased value in their native land, they cannot be exported to America, as they carry piroplasmosis.

Russia is the main supplier of Akhal-Tekes to America and Europe, and the organization that controls the stud book is based in Russia. MAAK.

BREED STANDARD

The Akhal-Teke breed does show much variety of form, from the solidly built dressage performers to the greyhound shape of the best race horses. However, MAAK’s website defines the ideal characteristics of the Akhal-Teke as follows:

- “Head: light, dry with wide lean lower jaw, straight profile or with convex forehead, prolonged facial part; big eyes with special slanting shape (slant-eyed) and overhanging superciliary arches; thin, mobile, high set up ears; thin lips and nostrils; long, wide poll. The head is set on the neck at acute angle.

- Neck: high set, long, straight or S-arched, round in cross-section, flexible.

- Body:

The withers: high, long, well-muscled.

The shoulder: long, slant set, with well-developed muscles

The upper arm: with normal slope, well-muscled

The chest: deep, wider behind shoulders, oval form, with long false ribs.

The back and loins: even, relatively wide, may be with some insignificant lengthiness

The croup: with normal slope, sometime a bit slopping, wide, long, and with strong muscles lowering well down to gaskin.

The tail: low and deep set, often practically hair-less at the dock

Legs: lean, long with well-developed joints and firm well-shown tendons, small strongly built hooves. The legs stand parallel to each other, feather are absence or very insignificantly present.

Muscles: flat, dense with long fibers

Coat: thin, silky, light main and tail, forelock and feather are absent or insignificantly present.

Movements: spacey, flexible, elastic, with good impulse, comfortable for rider at all gates; strong, flexible jump at flat trajectory and good style.

Colors: big variety of colors from black to cream, often with typical metallic shine – golden and silver.”

WHAT THOSE NAMES MEAN

Most Akhal-Tekes are named following the Turkmen tradition of using descriptive references.

Colors: Mele means dun; Kara, black; Dor, bay; Al, chestnut. A buckskin is called Aksakal, and is the most favored color.

Markings: Depel means white star, Burnak, white muzzle, Inche means white stripe and Ak Bilek, white sock.

Kush is also a common element of Akhal Teke names and means bird.

Find out more about all kinds of breeds in our sections on Horse Breeds and Health & Education.